The Supposed Decade of Flat Wages Was Worse Than We Thought

by Michael StephensIt’s well known that the wages of US workers have become disconnected from productivity growth, with real wages growing much more slowly than advances in productivity over the last several decades. This is a key part of the story of widening income inequality.

But these observed trends actually understate the degree to which working people have been left behind. New research reveals that the US economy is doing a worse job passing on productivity gains to workers than the wage growth (or even stagnation) numbers suggest.

The Levy Institute’s Fernando Rios-Avila and the Atlanta Fed’s Julie Hotchkiss looked back to 1994 and tried to see what proportion of real wage growth since then can be accounted for by key changes in the demographic profile of the labor force: principally, the fact that the average worker has become older (i.e., more experienced) and more educated.

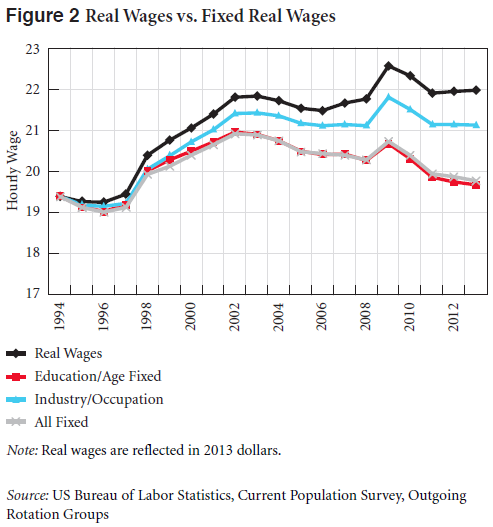

What they found is that over 90 percent of real wage growth between 1994 and 2013 was due to demographic shifts. And the 2002–13 period, commonly referred to as the decade of flat wages, is more accurately described as “a decade of declining real wages within age/education worker profiles.” If we control for demographics, wages are back to where they were in 1998. That’s what you’re seeing in the red line below:

Of course, generally speaking, the fact that we have a more educated workforce is good news. But we also want to know the extent to which workers with a particular demographic profile—workers with a given level of experience and/or education—are seeing increases in compensation as labor becomes more and more productive. “When describing the evolution of well-being in the population,” Rios-Avila and Hotchkiss suggest, “an official index for a ‘fixed’ wage trend might be more appropriate for policymakers.” Such an index would paint a disappointing picture of the last decade.

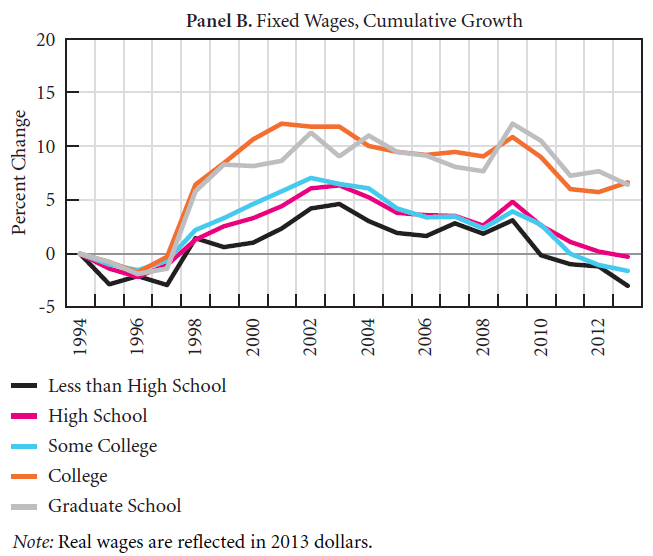

Since 2002, wages have fallen for workers at all levels of educational attainment (this is true whether or not we take ageing into account). And as you can also see in the next figure, when we control for changes in the age/experience profile within each educational grouping, workers without a college diploma are being paid less than they were in 1994 (the gradual erosion of their wages over 2002–08, combined with the recession and unimpressive recovery, have wiped out all the gains these groups at the lower end of the educational scale made from 1994 to 2002).

The authors also find that gender and racial wage gaps have shrunk by less than it may appear over the last decade, once we account for demographic changes. Controlling for shifts in the average age and educational attainment within each group allows us to disentangle reductions in pay inequality between male and female workers that are due to, say, women’s educational advancements outpacing men’s, from other sources of progress (or lack thereof) in gender-based wage inequality.

To see the full results, download their new policy note.