Unmasking Hidden Poverty in America: The Role of Time Deficits

by Ajit Zacharias, Fernando Rios-Avila, Thomas Masterson, and Aashima Sinha

What if Household Production is recognized as a necessity?

Imagine if unpaid work done at home—cooking, cleaning, childcare, eldercare[1]—were recognized as part of basic needs as, for example, a minimal quantity of food and clothing? Would it change how much poverty we find? An upcoming study by the Levy Economics Institute suggests it absolutely would.

The study augments the traditional poverty line by considering the minimal time required for unpaid work. Families that do not have enough available time to set aside for unpaid work requirements will have to purchase market substitutes to maintain a budget reflected in the traditional poverty line. Adding the cost of such market substitutes to the standard poverty line results in a time-adjusted poverty line which underpins our flagship metric the Levy Institute Measure of Time and Income Poverty (LIMTIP). Through a series of studies, we have developed LIMTIP estimates for Argentina (2005), Chile (2006), Ghana (2012–13), Korea (2009), Mexico (2008), Tanzania (2011–12), Turkey (2006), Ethiopia (2015), and South Africa (2015).

We estimate LIMTIP for the United States for the first time and the measure reveals that poverty in the U.S. is far more widespread than conventional, official poverty measures suggest, and in fact exposes inequality across multiple dimensions: gender, race, class, and family structure.

What is Time Poverty — and Why Does It Matter?

American culture celebrates productivity and hard work, but behind these values lies a hidden reality: many households juggling employment and household responsibilities face time poverty that traditional metrics fail to capture. This new research from the Levy Economics Institute sheds light on this overlooked dimension of economic hardship.

Time poverty refers to the situation where individuals lack sufficient time to meet basic household and care responsibilities without compromising their own physical and mental well-being. This is mostly relevant for employed individuals who face time deficits—meaning they do not have enough hours in the day to balance paid work and household production without sacrificing personal care time (the minimum time required for activities such as sleep, personal hygiene, eating and drinking, etc.).

The significance of household production cannot be overstated at the macro and micro economic levels. According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, including the value of household production would have increased GDP by approximately 25% or $5.32 trillion in 2020. Another, Levy Institute study, commissioned by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), found that household production provides services worth about 63% of average monthly consumption expenditures by U.S. households in 2019.

The Hidden Poor and the Time Poor: How Traditional Measures Fall Short

By monetizing time deficits in household production and adjusting poverty thresholds accordingly, the re

searchers uncover the “hidden poor” — individuals/households who do not appear poor under traditional poverty measures but earn incomes that fall below the adjusted poverty line. Apart from its impacts on income poverty, time poverty

should be considered as an independent dimension of deprivation as well. The study finds that time poverty disproportionately affects women, married individuals, and parents, adding another layer of vulnerability that is often missed in standard poverty measures like the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). As shown in previous Institute research, commissioned by the U.S. BLS, a staggering 78% of all household production in 2019 resulted from women’s work. This disparity in turn is reflected in time poverty rates.

The upcoming study uses the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) and the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to develop a synthetic dataset based on a statistical matching procedure and provide some striking results:

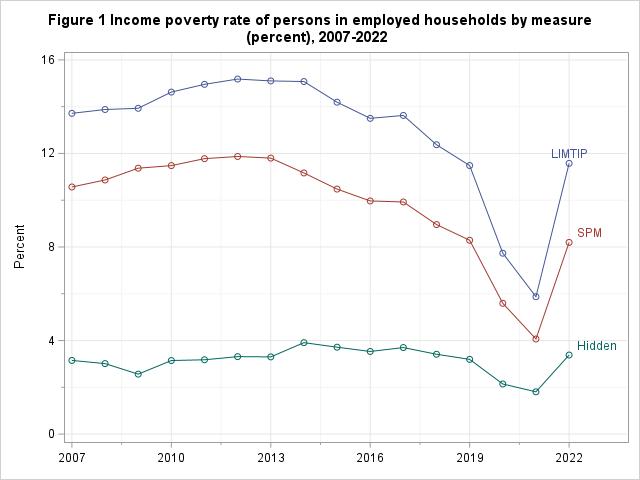

- Higher Poverty Rates: On average, LIMTIP poverty rates exceeded SPM poverty rates by about 30% between 2007 and 2022 (Figure 1) among employed households[2]. This means about 3% of the population—mostly women and parents—remained hidden in standard poverty measures.

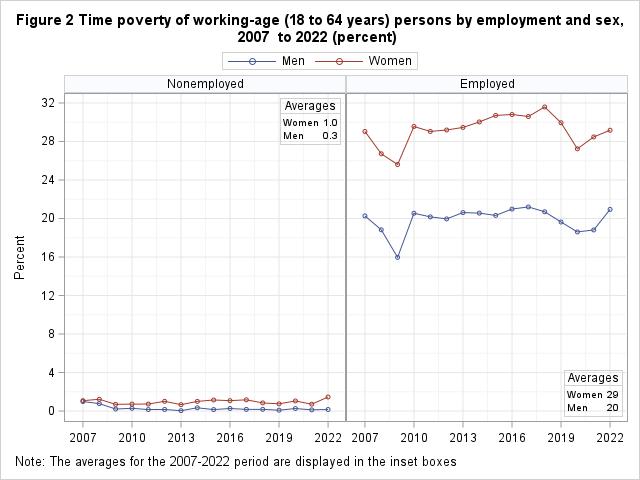

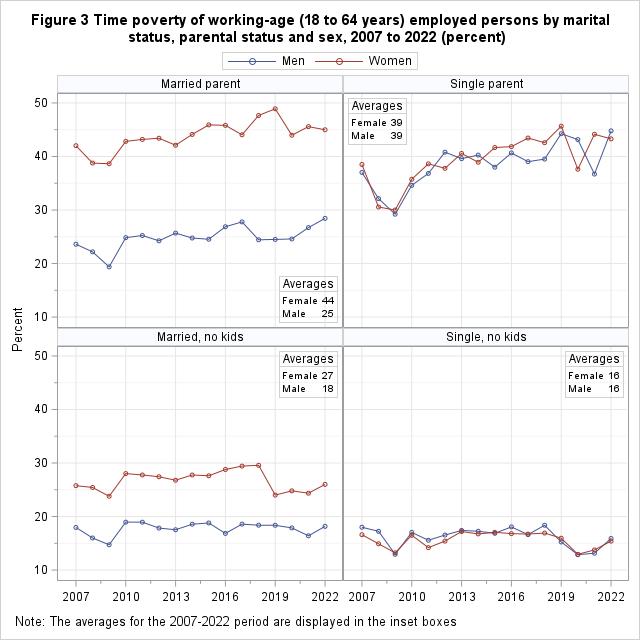

- Gender Disparities: Employed women face 9 percentage points (pp) higher time poverty than their male counterparts (Figure 2). For married women with kids, the time poverty gap soars to 19 pp compared to married men with kids. Meanwhile, single men and women experience comparable time poverty rates of around 39% (Figure 3).

- Parenting Penalty: Parents, especially mothers, bear the brunt of time deficits (Figure 3). The demand for unpaid childcare and domestic work leaves many working mothers time-poor despite earning incomes above the poverty line.

Why This Matters for Policy

The findings call into question the accuracy of conventional poverty measures that focus solely on income without accounting for unpaid work. Policies aimed at reducing income poverty often overlook the time squeeze faced by working individuals, particularly women and caregivers.

This yields profound suggestions for social policy, including:

- Expanding access to affordable childcare to reduce time poverty.

- Implementing paid family leave to alleviate the unpaid care burden.

- Promoting workplace flexibility to support working parents and caregivers.

- Increasing minimum wages and reforming income support programs

- Promoting collective action (expanding union coverage) for better pay and working conditions

Without addressing the time constraints experienced by low-income and time-poor individuals, traditional anti-poverty programs risk falling short in their effectiveness.

Revealing the Full Picture

By integrating time deficits into poverty measurement, the LIMTIP framework provides a more accurate and inclusive understanding of poverty in the U.S. economy. It also underscores the deeply gendered nature of unpaid care work—disproportionately borne by women—that continues to undermine economic well-being.

This study challenges policymakers to rethink poverty interventions—not just by boosting income but also by recognizing and redistributing unpaid work. The future of economic well-being lies not only in wage growth but also in addressing time constraints and gender unequal sharing of work.

By elucidating the often overlooked economic role of household labor, our research draws attention to addressing poverty by emphasizing both monetary resources and the distribution of unpaid work—particularly the gendered dimensions of care work that remain largely invisible in conventional economic analyses.

The LIMTIP framework provides a more nuanced understanding of economic well-being that can guide the development of more effective anti-poverty policies in the US and globally. As we continue to navigate economic challenges, acknowledging these hidden dimensions of poverty will be essential for creating a more equitable society.

For a deeper dive into the findings including further dimensions of race and gender intersections, stay tuned for our upcoming policy brief / full report, available soon at Levy Institute’s website [here].

[1] We are referring to the “substitutable” unpaid household production activities, which includes domestic chores and care provisioning.

[2] Employed households as households with at least one employed person of working age (18-64).