By Dan Monaco

The Straddler, Fall 2011. All content © The Straddler

I

The events leading up to and following the financial crisis in 2008 led to widespread deployment of the term “Minsky Moment,” used to describe the painful termination of what Hyman Minsky called “runaway expansion.” In boom times, according to Minsky, stable profit growth resulting from speculative (debt-fueled) risk-taking leads to ever greater speculative risk-taking until the bubble finally bursts and a debt-deflation crisis ensues as investors liquidate their assets to cover their debt liabilities. The longer the “runaway expansion” lasts, the more dramatic the “Minsky Moment” is liable to be.

In June I traveled to the Minsky Summer Seminar at the Levy Institute at Bard College. The train stop closest to Bard is Amtrak’s Rhinecliff station, and the journey to it from New York City takes you up the eastern bank of the Hudson River for about ninety minutes. It’s hard not to be struck by the beauty of the Hudson, broad and grand between its beveled cliffs, a steady, workmanlike current, simultaneously fierce and serene, operating like a paradoxically silent operatic ostinato. Pleasure cruises run between New York City and Albany, and it is not unusual to see a barge heading in this direction or that, evoking the Hudson Valley’s manufacturing history.

Of course, the Hudson River is also infamous for its having been contaminated by toxic polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) from General Electric’s manufacturing plants in Hudson Falls and Fort Edward. The result of years of mostly legal dumping of PCBs between 1947 and 1977 led to a large stretch of the river being declared a Superfund Site in 1984. Turmoil, controversy, and legal battles ensued; cleanup dredging began in earnest in 2009.

Knowing this as one looks out a railcar window at the river leads to an odd and occasionally eerie appreciation of the scenery. It might also inspire a thought or two on the occupation of the economist. For there is a sense in which all economists are implicitly charged with advancing recommendations on the appropriate use of an apparatus—call it the labor and money arrangements of man—which one might with only slight exaggeration describe as a sort of savage machinery. This apparatus is capable, when adequately structured, of advancing human well-being; it is capable, too, of setting well-being back, of passing over certain sections of humanity—including populations within nations, nations themselves, continents, and generations.

But there is also a sense in which, at least to the eyes of an outsider, the codes of the profession, and the dominant modes of thought within the field, seem to put the economist who fully acknowledges the potency of the poorly secured munitions ship whose course he is seeking to influence in a bit of an odd position. If he thinks it is best to grapple with the navigation plan, he must still contend with the tendencies of the moiety of his brethren who, in spite of the field’s outsized political and cultural influence, either deny that their conclusions have anything to do with something as complex as the actual practice of seafaring, or who—hewing closely to the field’s first principles—regard an absence of captaincy as the best captaincy, the rarely manned bridge the best manned bridge.

“Economists have lost their credibility because they do not actually deal with the real world,” Dimitri Papadimitriou, President of the Levy Institute, told me in my conversation with him. “But there were and are certainly some economists, including Hyman Minsky, who looked at the real world not as an exception case.”

“Minsky was in some ways a pioneer. He saw that economic theory assumed that everything is known and that there is some tendency of the system to reach for equilibrium and, at times, to reach periods of ‘tranquility,’ as he preferred to call them. Of course, he never believed that stability was possible. He didn’t believe in the invisible hand. There’s a reason why it’s invisible—because it’s not there.”

II

It is characteristic of capitalism, according to Minsky’s John Maynard Keynes, that it fails to maintain full employment,(1) and that its most essential traits are instability and uncertainty.

JMK appeared in 1975, just as the postwar “Golden Age” of global capitalism was coming to an end in a decade marked by oil shocks, unsustainable levels of inflation, the dismantling of the Bretton Woods international monetary system, rising rates of unemployment, and growing popular familiarity with the concepts of “stagflation” (stagnation and inflation) and the “misery index” (unemployment plus inflation).

The 1970s were a crucial period for both economic policy and economic study; the decade’s disruptions were exhibited to impugn the effectiveness of, and ultimately abandon mainstream adherence to, Keynesian economics. As Peter Temin, an economic historian at MIT, told The Straddler in February, there were two reactions within economics to the problems of the 1970s: “One was to patch up [Keynesian] theory and extend it. The other came from people who said that Keynesian theory is terrible—it got us into this mess, we have to do something different. And that fed into this desire to use mathematics to set up elaborate models and to have everything be efficient."(2)

It led, in other words, to the recrudescence of precisely the sort of clean neoclassical models of efficiency, equilibrium, and omniscience from which Keynes, in 1937, had broken by publishing The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.

The return back to neoclassical economics, however, was made easier by its never having really left. The Keynesianism prevailing for a time before, and for the thirty years after, the second World War was in fact a neoclassical synthesis of old ideas and new theory.

In Minsky’s recap of the standard telling, the process of synthesis began with J.R. Hicks’ influential 1937 article “Mr. Keynes and the ‘Classics’,” which introduced an interpretation and a simplified model (IS-LM) by which to understand Keynes. Hicks’ interpretation was the foundation of the influential economist Alvin Hansen’s work “in hammering out the American version of standard Keynesianism."(3) As a result, American (and a great deal of international) economic policy was guided by a neoclassical synthesis called Keynesianism into the 1970s.

Without getting into the neoclassical synthesis’ IS-LM model (which examines the relationships between interests rates and GDP), or the intricacies, such as they are, of neoclassical Quantity Theory (which essentially argues that prices are exclusively related to the amount of money in circulation), the fundamental difference between Keynesianism (whatever the version) and neoclassical theory is that the former argues that some form of government intervention into the economy is necessary to achieve full-employment stability, while the latter holds, to use Minsky’s words, that “a decentralized economy is fundamentally stable."(4)

Johan Van Overtveldt’s history of the Chicago School provides a succinct summary of the worldview underlying neoclassical theory:

The basic assumption of neoclassical economic theory is the proposition that in a competitive market environment, individuals and corporations pursuing their own self-interests necessarily promote the best interests of society as a whole.(5)

Thus, neoclassical economics, whatever its modifications or adjustments, is always in essence a cry for “pure” capitalism, while Keynesianism, whatever its color, is always at heart a proffered solution (more or less “radical,” depending upon one’s interpretation) to the problems of capitalism from within capitalism.

In JMK, Minsky writes that in the 1930s, neoclassical economics had held that events like the onset of depressions were anomalies; once they began there was nothing to do but ride them out. Coming from a different direction, orthodox Marxists “interpreted the Great Depression as confirming the validity of the view that capitalism is inherently unstable. Thus, during the depression’s worst days, the mainstream of orthodox economists and the Marxists came to the same policy conclusions: …nothing useful could be done to counteract depressions."(6)

The General Theory was thus simultaneously a response to worldwide depression, a dramatic (if not a clean) break with neoclassical economics, and an argument that while capitalism is “inherently unstable,” policy solutions from within do exist to ensure that “business cycles, while not avoidable, [can] be controlled."(7)

What made Keynes’ theory possible, in Minsky’s view, was a radical paradigm shift in perception that placed the “fragile” workings of the financial sector at the center of a complex modern capitalist economy:

Whereas classical economics and the neoclassical synthesis are based upon a barter paradigm—the image is of a yeoman or a craftsman trading in a village market—Keynesian theory rests upon a speculative-financial paradigm—the image is of a banker making his deals on a [sic] Wall Street.(8)

In this capitalist economy, full-employment equilibrium—indeed, equilibrium in general—is not possible because each stage of the business cycle contains the loose strands of its own unraveling. Actors operating in a sophisticated financial sector are engaged in “decision-making under conditions of intractable uncertainty” and as a result there are always “processes at work which will ‘disequilibriate’ the system."(9)

Financial collapses are the most pronounced examples of these disequilibriations:

[T]he financial system necessary for capitalist vitality and vigor…contains the potential for runaway expansion, powered by an investment boom. This runaway expansion is brought to a halt because accumulated financial changes render the financial system fragile, so that not unusual changes can trigger serious financial difficulties.… [S]tability…is destabilizing.(10)

III

What of Minsky’s claim that Keynes was basically misinterpreted by mainstream economics? And what of this claim in the context of capitalism’s “Golden Age?” Whether or not the neoclassical synthesis was an accurate interpretation of Keynes, the thirty years following World War II were notable in the history of capitalism for their relatively stable growth and their approximation to full employment. I put these questions to Papadimitriou.

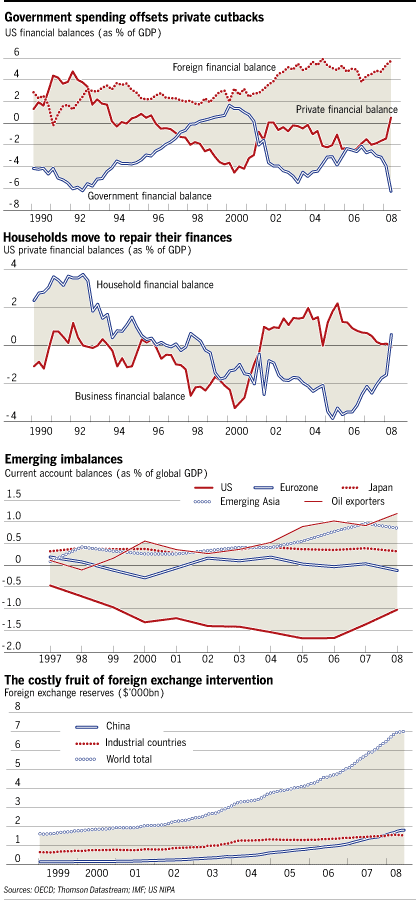

Papadimitriou: Minsky realized that there were some important features that prevented a full-blown crisis from occurring. There were a number of near crises, but Minsky would agree that during the “Golden Age” there was a crucial role that both big government played as well as the big bank [i.e., the Federal Reserve].

Minsky was always interested in what is apt policy versus what particular item one should look for in a policy. Minsky’s own policy was that if you believe stability is destabilizing—that is, there is a tendency for the system to destabilize—you need to be prepared for that and do something about it to prevent it.

Yes, you can assume that private markets can be self-regulating as a result of profit seeking—you don’t want anything bad to happen. But on the other hand, we know that avarice and greed become a lot more important than self-restraint and self-regulation. So my suspicion is that Minsky would have said that you have to be able to rely on something other than policies emanating from traditional economic theory, like the neoclassical synthesis. As, for example, in the same way as Schumpeter had said that there will always be technological innovation, and therefore you will have creative destruction, Minsky was cognizant of financial innovation. And, there is a need, then, for sophisticated instruments of regulation that are required to keep up with financial innovation, especially if you believe that a sophisticated economy as ours is more or less a finance-guided economy. Look what has happened especially now, where the free-market mantra took hold beginning with the Reagan Presidency. Look at the results.

Had Minsky been alive today, he would have said that government doesn’t only have to play a role in expenditures [to generate adequate aggregate demand], but also, a role in industrial policy. And that has been absent. The American economy is superior to other economies in terms of high technology, aerospace, and probably agriculture. But you cannot sustain growth to provide for 300 million people [on these industries alone].

In addition to emphasizing that “there is no final solution to the problems of organizing economic life,"(11) Minsky argued that policies based on a correct interpretation of Keynes would direct government expenditures towards more socially and individually productive ends, and would also promote a more equitable distribution of income. Writing as the neoclassical synthesis was on the verge of giving way, he lamented the military spending and empty consumption of capital-intensive goods that had marked its heyday.

As Keynes summarized The General Theory, he avowed that there were two lessons to be learned from the argument. The first was the obvious lesson that policy can establish a closer approximation to full employment than had, on average, been achieved. The second, more subtle, lesson was that policy can establish a closer approximation to a more logical and equitable distribution of income than had been achieved.

To date [i.e., 1975] the first lesson has been learned, albeit in a manner that makes an approximation to full employment heavily dependent upon government spending in the form of defense production and private investment that sacrifices present plenty for questionable benefits in the future. … [T]he second lesson has been forgotten; the need for policy aimed to achieve justice and equity in income distribution has not only been ignored but it has been so to speak turned on its head.(12)

Raising questions of income distribution and inequality in America tends to lead, in both elite and barroom discourse, to cries of “class warfare” or worse, so I asked Papadimitriou to elaborate a bit on Minsky’s idea of equality in the context of the reality of default American economic ideology.

Papadimitriou: Minsky was very concerned about poverty. He thought the government should approach the poor from the perspective of, “why are they poor?” and seek to restructure the view about what government should do. He was against the idea of government transfers to alleviate poverty. He would have been intolerant of the government’s failure to do now what was done during the Great Depression through employment programs such as the Works Progress Administration and other programs of the New Deal, because he thought that by giving the poor these transfers the government changed their behavior as opposed to providing them with a job—giving them a goal and, to some extent, the capacity to enjoy a standard of living and social inclusion.

Minsky was realistic that the sort of equality connotated by the word “equality” is not achievable—it wasn’t achieved under socialism; it wasn’t achieved under communism. But, nevertheless, the question is, is it appropriate for one-tenth of the population to control that gigantic percentage of wealth, and to command that kind of income, relative to the bottom half, which basically does not have a chance to realize the prosperity that can be achieved in this country.

You can put it in a different way. The government plays the role of a redistributive vehicle. As an example, Minsky and others would be appalled at the Bush tax cuts being continued. They don’t do anything for aggregate demand, they don’t do anything in terms of increasing employment, and they don’t do anything in setting the economy on a path for growth. Therefore, Minsky would have insisted that these tax cuts cause the wrong kind of debt for the government to incur. He would have suggested other policies—for example, promulgating a tax structure that is progressive and not, like the payroll tax, regressive—that could bring about better outcomes. That would not lead to the same maldistribution of wealth we are experiencing currently.

But what about the perception of this maldistribution of wealth? There seems to be an odd phenomenon, arguably not limited to American society, by which the reality of discontent with income and wealth maldistribution is held in check by ambivalent feelings about to what degree it is actually malevolent. Back in April, former U.S. Senator Phil Gramm authored an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal in which he argued that Barack Obama’s presidency had brought about “higher taxes on the most productive members of American society."(13) This is a familiar stance on the right that is not wholly rejected by the population at large: the wealthy may create abundant riches for themselves, but they are the job creators who provide us with employment, and so anything we do to hurt their bottom line just ends up hurting our own. Or, even if that’s a bit hard to take, in any case, any remedy the government would come up with to address maldistribution would be worse than the malady itself.

And this ambivalence has an additional, aspirational contour. There is a famous quote, attributed to John Steinbeck, that runs, “Socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.” I asked Papadimitriou if, putting the question of socialism aside, he thought the attitude towards the rich by the poor was in some ways informed by their seeing themselves not as the poor, “but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.”

Papadimitriou: The majority of the population has that perspective, and that comes out clearly in the surveys that are run on individuals who are surviving on welfare checks and yet are against taxation because they believe there could be a time that they will be hurt. There is this longing, to go back to Steinbeck’s words, to become a millionaire.

On the other hand, there is another group of the population that is totally disenfranchised, and I doubt that these people have any notion that they will ever actually find a ticket out of their misery. You can see that in the inner cities, and in the increase of homelessness.

IV

With respect to creating a culture that is receptive to the idea that there is a role for the government in promoting a more equitable society, the challenge faced by people like the Minskians is fourfold. First, a significant portion of the population at large must agree that the so-called “American Dream” is not alive and well. As Papadimitriou told me, “the ‘American Dream’ is fulfilled only for a segment of the population. Maybe the one percent in the income distribution ladder.”

Second, this same portion of the population must accept that the receding of the “American Dream” is not a result of government malfeasance but has its roots in the present structure of the system in which private actors operate.

Third, there must be widespread willingness to accept that government has a place in bringing about better economic outcomes and more equitable distributions of income.

Fourth, people must be willing to act on these beliefs to press the government to take action. (For all its myriad failings and inefficiencies, the government possesses a quality unique among powerful entities in that it is subject to some form of democratic accountability.)

Just how challenging the current ideological climate makes all of this was well encapsulated in an exchange that took place in July between Paul Krugman and George Will. Just after word emerged of a pending agreement between the House, Senate, and President to raise the ceiling on federal debt in exchange for spending cuts and budgetary reductions, both Will and Krugman appeared on the “roundtable” segment of ABC’s This Week:

Krugman: We used to talk about the Japanese and their lost decade. We’re going to look to them as a role model. They did better than we’re doing. This is going to go on—I have nobody I know who thinks the unemployment rate is going to be below eight percent at the end of next year. With these spending cuts it might well be above nine percent at the end of next year. There is no light at the end of this tunnel. We’re having a debate in Washington which is all about, “Gee, we’re going to make this economy worse, but are we going to make it worse on ninety percent of the Republicans’ terms or a hundred percent of the Republicans’ terms?” And the answer is a hundred percent.

Will: Paul’s right, we are a third of the way to a lost decade. But we’re a third of the way after TARP, the stimulus, Cash for Clunkers, dollars for dishwashers, cash for caulkers, the entire range of stimulus—the Keynesian approach which, by its own evidence, simply hasn’t worked. Now, Paul would double down—

Krugman: In advance—one important point to make is that people like me said, in advance, this wasn’t remotely big enough. It’s not an after the fact—

Will: That’s true.

Krugman: —it’s not coming back afterwards. Right from the beginning, I looked at the numbers—people like me looked at the numbers and said, we’re going to have cutbacks at the state and local level, you’ve got a federal increase which is going to be barely enough to limit those cutbacks. There’s going to be no net fiscal stimulus if you look at government as a whole, which is what happened. So here we are.

Will: It would be good to go to the electorate and have a Krugman election this time, saying, “Resolved, the government is too frugal. Let’s vote."(14)

And so, even in the face and fallout of a disastrous economic collapse brought about by a financial crisis that occurred in the maw of an era of pronounced deregulation and government rollback, the burden of proof remains on anyone who would argue that properly calibrated government intervention into the economy is not only necessary, but is also capable of producing more positive outcomes. (It is, of course, worth noting that many forms of government expenditure—defense and less visible subsidies and tax incentives for large businesses and wealthy individuals being obvious examples—are somehow exempted from categorization as government intervention into the economy.)

Thus, Will, who is somewhat rare among contemporary conservative commentators in broadcast media in that his is the professorial posture of a man who likes to take his arguments on the plane of ideas, was quite comfortable responding to Krugman’s points with nothing more than an arched rhetorical eyebrow, confident (not without cause) that such a response was all that was necessary to refute the most modest and elementary recommendations derived from Keynesianism.

In responding to a crisis which they agree calls for a basic Keynesian response, then, left-of-(rather conservative)-center political actors and analysts (Larry Summers, for example—a hedge-fund liberal and the most prominent embodiment of the “New Keynesian” heirs to the neoclassical synthesis, who was instrumental in developing the partially effective stimulus bill of 2009, and who was also an ardent supporter of financial deregulation in the 1990s—called for additional stimulus in 2011) find themselves in a circular process by which they are:

constrained by politics and ideology which → limits the force of the response which → leads to outcomes that partially attenuate but do not end the crisis which → allows opponents who have helped build constraints on a potential Keynesian response to claim to demonstrate that Keynesianism does not work which → builds even more confining constraints on its application.

And, if, returning to Minsky, he is correct that Keynes has been misinterpreted, the process above is, in some ways, the same process that Keynesianism itself underwent during, and immediately following, the reign of the neoclassical synthesis.

V

Why should Keynes’ theory have “triggered an aborted, or incomplete, revolution in economic thought?” Minsky offers a number of reasons. He suggests, for example, that The General Theory is a “clumsy statement” (“a great deal of the new [theory] is imprecisely stated and poorly explained”); that Keynes’ didn’t have a chance to participate in the interpretative debate following its publication (he was sidelined by a heart attack and then went to work in the war effort); and that it is not possible to perform controlled experiments in the social sciences (a familiar lament).(15) But two of Minsky’s explanations in particular stand out.

1) According to Minsky, “the older standard theory, after assimilating a few Keynesian phrases and relations, made what was taken to be real scientific advances.”

Even though economists had often argued as if the laissez-faire proposition, about the common good being served as if by an invisible hand by a regime of free competitive markets, were firmly established, it is only since World War II that mathematical economists have been able to achieve elegant formal proofs of the validity of this proposition for a market economy—albeit under such highly restrictive assumptions that the practical relevance of the theory is suspect.(16)

Keynes was therefore “made to ride piggy-back on mathematical general-equilibrium theory.”

As an outsider, it is hard not to see in this assimilation a manifestation of a broader tendency in mainstream economics to reach for an equilibrium of another kind. The au fond assumption away from which the field, generally speaking, seems to resist being pulled, and towards which it inevitably claws its way back, is precisely the neoclassical proposition Van Overtreldt describes in the citation above.

Of all of the social sciences, famously incomplete in their ability to comprehend human affairs, economics seems to be the least capable of acknowledging its limitations—or perhaps it is simply the most skilled at cagily hedging those limitations. After all, it seems reasonable to assume that the economic affairs of man are a complex affair, full of inconsistencies, contradictions, and odd behavior. Messy, in other words. And yet, it appears that theories within mainstream economics seeking to account for this mess—or seeking to counter the deleterious consequences of this mess—are at best partially assimilated, and at worst, wholly rejected in favor of models and modes of thought that don’t just envision and promote the benefits of the competitive workings of free and unfettered markets, but that also create an ideal out of them.(17) Further, any deviation is met with a redoubled effort to reinforce and/or retrofit the ideal. As Peter Temin told The Straddler, “The kind of models that many people use—general equilibrium models—start from assumptions of perfect competition, omniscient consumers, and various like things which give rise to an efficient economy. As far as I know, there has never been an economy that actually looked like that—it’s an intellectual construct."(18)

James Kenneth Galbraith’s words to The Straddler back in March of 2010 are of a similar flavor—and go further towards hinting at an explanation of why this might be:

[W]hen we encounter a doctrine of harmonization, of the smoothly functioning realization of the interests of all, the great and the small, which is textbook market economics, people should recognize that this is sand being thrown in their faces—that this cannot possibly be a realistic representation of the world in which we actually live. Take it as an analytic principle that one has to look at the behavior of the great with a cold eye.(19)

There is a famous and oft-cited quote of Keynes from The General Theory which runs:

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas.

Minsky agrees and disagrees, proposing that this quote “needs to be amended to allow the political process to select for influence those ideas which are attuned to the interests of the rich and powerful.” That is, ideas are important, but those ideas best suited to the advance and further entrenchment of the “vested interests” are often selected as the most important.

Perhaps it is this process, beyond the limitations of the field qua investigative social science, that accounts for mainstream economics’ radical idealism with respect to the functioning of capitalism.

2) But there is a further point to be made, using the final potential reason Minsky lists for the failure of full-throated Keynesianism to take hold as a point of departure:

[T]he Keynesian Revolution may have been aborted because the standard neoclassical interpretation led to a policy posture that was adequate for the time. Given the close memory of the Great Depression in the immediate post-World War II era, all that economic policy really had to promise was that the Great Depression would not recur. … Questions as to whether the success of standard policy could be sustained and questions of “for whom” and “what kind” and about the nature of full employment were not raised. The Keynesian Revolution may have been aborted because the lessons drawn from the standard interpretation not only did not require any radical reformulation of the society but also were sufficient for the rather undemanding performance criteria that were ruling.(20)

One wonders—in an age of florid and ever-increasing income inequality, stagnating wages for the majority of Americans, the recent development of high and persistent unemployment, and the pronounced deterioration in the quality of experience for the citizen as laborer (not only has job security disappeared, but the erosion of benefits for members of the workforce has increased as a structural adjustment of the meaning of employment continues apace) and for the citizen as consumer (interactions with providers of goods and services leave the consumer not infrequently in a netherworld between simultaneously complex, shoddy, and quickly obsolete products and poor, generally unresponsive support service)—if the implementation of an effective method to remedy the recent trajectory of economic citizenry would now require a radical reformulation of society. Or, what is more likely, if a change in society’s structure that, while not particularly radical, would be perceived as radical by those who have benefitted most from its current arrangements. Perhaps this is why Barack Obama’s speech on September 19th, in which he issued recommendations for tax increases on high-end incomes, and which contained a knowing and preemptive rhetorical strike against those who would call it class warfare, was greeted with cries of class warfare. (Class warfare, incidentally, is a concept with notable and defining instances in the actions of mankind. Examples in modern history include the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, the Chinese Revolution, and America’s nineteenth-century labor battles. None of these events or movements seem to have had at its vanguard a battering ram in the shape of a modest tax increase.)

While a small sector of the society has been well served by the workings of America’s economic system, the vast majority of the population has reason for discontent. One suspects that this might become even more the case as the future unfolds. Under these circumstances, if you’re interested in defending the status quo, better to fight on the plane upon which you are strongest by wrapping yourself in the rhetorical trappings of American economic ideology and the reassuring tropes of American self-identity than to join the battle on the plane of real-world outcomes and conditions.

And better, too, if you are an economist with a stake in the game—a little too cozy, perhaps, with those who foot the bills, but by no means operating outside of the ethics of the field in which you ply your trade—to retreat to models demonstrating the fundamental correctness of your position, even if these models, in the end, have a dubious relationship to the actual world.

VI

It should be noted that in some ways, Minsky’s pessimism about the possibilities for stability within capitalism, may prove—subsequent to the 2008 “Minsky Moment”—too optimistic for present circumstances.

Speaking extemporaneously on a panel at the Levy Institute in June, the Washington University economist Steven Fazzari pointed up the potential for a cycle to get stuck at a particular stage:

What’s the converse of “stability is destabilizing?” Instability is stabilizing. I don’t know that Hy[man Minksy] would have ever said that, but the theory does imply this to some extent because it is a theory of indefinite cycles. So you get the boom, you hit the peak, you get the crisis, the crisis is cleansing—it may be extremely painful, but you wipe out the weaker units and you reestablish the conditions for growth again when the balance sheets are in some sense repaired. I think that’s the basic theory, the basic story.

So in that context, if you want to tie my question—what will be the aggregate demand generating process going forward—to a Minsky perspective, you have to ask how long will it take for balance sheets to be repaired? How long will it be until more robust conditions in the financial system are established?

A necessary condition for a more robust recovery is the improvement of the household balance sheet—leading to a restoration of better consumption, given that consumption is such a big part of demand. But I’m actually not fully convinced that this is sufficient. It’s necessary, but I’m not sure it’s sufficient.

Income distribution is a fundamental structural problem that goes beyond finance. The growth model in the US over the past three decades was one of relatively stagnant income growth across much of the income distribution, plugging the hole in demand with more consumer borrowing. So balance sheet improvement can help but it doesn’t seem to me that it deals with the additional issue of the income distribution. And there’s nothing on the table from a policy perspective or a structural perspective that would change this.

In other words, absent some significant event or dramatic change in policy, the fuse may have blown on the washing machine, leaving us stuck on soak.

Paul Davidson, editor of the Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, made a similar argument in his remarks at the Institute:

From the end of World War I to the beginning of World War II, the unemployment rate in the UK was double digits, except for one year when it was 9.7. That doesn’t sound like a cyclical problem to me, and it didn’t sound like it to Keynes, who basically argued that the economy had settled down at a long-run, stable unemployment rate which was very high. Just look at Japan in the 1990s and 2000s—and, I’m afraid to say, maybe a decade or two in the United States, beginning in 2007. So it’s not the ups and downs of a roller coaster—the capitalist system can be stable at less than full employment.

No one can know what will happen as the avenues to affluence and the economic expectations (be they grand or modest) that people have for their lives are more and more ostentatiously occluded for more and more members of the population. It’s not likely to be pleasant, as grievances tend to manifest themselves in all sorts of odd and often irrational ways (the Tea Party being Exhibit A in our own times). But it’s also always possible, of course, that the worm will turn and those who benefit least will fix their attention on those who benefit most. Perhaps this is American capitalism’s fundamental anxiety—indeed, perhaps it always has been. But in the aftermath—and in the midst—of its greatest crisis in eighty years, a heightened unease may help account for its pronounced defensiveness,(21) and the rigidity of its scholarly underpinnings.

VII

There remain broader questions. Though we are in a tough spot today partially because consumers are less able to play their accustomed role in demand generation, Minsky’s speculation that “[t]he joylessness of American affluence may be due to the lack of a goal, the acceptance of a standard in which ‘more’ is really not worth the effort"(22) rings no less true in these circumstances.

As of 1975, according to Minsky, “[t]he combination of investment that leads to no, or minimal net increment to useful capital, perennial war preparation, and consumption fads [had] succeeded in maintaining employment.” But though the period of the “Golden Age” had been remarkable in purely quantitative economic terms, in America it had “put all—the affluent, the poor, and those in between—on a fruitless inflationary treadmill, accompanied by…deterioration in the biological and social environment."(23)

And so, even if we accept that an economy should be geared towards full-employment with stable growth, a reasonably equitable distribution of income, and the potential to enjoy prosperity and affluence as goals, what form will this growth take? What do we mean by prosperity and affluence? And what are qualitative contours by which to gauge the well-being of members of our society?

At a time where a move back to some contemporary approximation of the moderate principles underlying the neoclassical synthesis would be regarded as radical, perhaps it is worth putting these larger, qualitative questions on the table as well.

Perhaps, too, it is time to urge the field of economics to wrestle with the complexity of a system whose limitations it is best not to elide in simplified models that have a Panglossian sanguinity at their core. And perhaps too it would be well to investigate the complexities that are actually produced by the limits of the capabilities of field.

For, as Minsky writes as he closes JMK, if, like Keynes, we think it best to live under an economic system “that sustains the basic properties of capitalism,” it should not be “because of the virtues of unfettered capitalism but in spite of its defects, which, though great, can in principle be controlled. ...[I]f capitalism is to be controlled so that the basic triad of efficiency, justice, and liberty is achieved, then the design of the controls will have to be enlightened by an awareness of what was obvious to Keynes—that with regard to both the stability of employment and the distribution of income, capitalism is flawed."(24)

Notes

1. “Full employment” is generally understood to mean a situation in which every person of working age who wants to work has a job, which is of course different than saying every person of working age has a job. In practical terms, unemployment rates below three, four, or even five percent—like those seen in the 50s and 60s, and again in the 90s—have typically been considered reasonably close approximations to full employment, not least because of the perceived relationship between low unemployment rates and the danger of an “overheating” economy leading to high rates of inflation. Indeed, there is a not uncontroversial concept in economics, the NAIRU (Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment), which argues that there is a rate of unemployment (sometimes infelicitously termed the “natural” rate of unemployment) below which an economy ought not go lest it risk unsustainable rates of inflation. It is a subject of some debate precisely what this rate is, or if it is the same rate at all times, or if it is even a useful concept, but it’s typically claimed to be in the neighborhood of five percent.

It is also worth noting, of course, that the official rate of unemployment is always lower than the actual rate of unemployment because official measurements fail to include significant portions of the nonworking population. For example, in September of 2011, the unemployment rate in the United States stood at 9.1 percent, or 14 million, according to the Department of Labor. But there were an additional 2.5 million, or 1.6 percent, who were officially not counted (how many were unofficially not counted is another matter):

“In September, about 2.5 million persons were marginally attached to the labor force, about the same as a year earlier.… These individuals were not in the labor force, wanted and were available for work, and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months. They were not counted as unemployed because they had not searched for work in the 4 weeks preceding the survey.…

“Among the marginally attached, there were 1.0 million discouraged workers in September…. Discouraged workers are persons not currently looking for work because they believe no jobs are available for them.”* (*United States Department of Labor. Employment Situation—September 2001. Washington D.C.: Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf [bold type in original].)

The so-called “underemployed,” people who would like to work full time but are working in part-time jobs, are also not included in official measures of unemployment.

2. “What’s Natural? Peter Temin in Conversation with The Straddler.” The Straddler, springsummer2011. http://www.thestraddler.com/20117/piece5.php

3. Minsky, Hyman P. John Maynard Keynes. New York: McGraw Hill, 2008. 32.

4. Ibid. 2.

5. Overtveldt, Johan van. The Chicago School. Evanston, IL: Agate B2, 2007. 52.

6. Minsky. Op. cit. 6

7. Ibid. 7.

8. Ibid. 55.

9. Ibid. 11, 59.

10. Ibid. 11.

11. Ibid. 166.

12. Ibid. 158.

13. Gramm, Phil. “The Obama Growth Discount.” Wall Street Journal. 15 Apr 2011.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703983104576262763594126624.html [my emphasis].

14. “Roundtable.” This Week with Christiane Amanpour. ABC: 31 Jul 2011.

http://abcnews.go.com/ThisWeek/video/roundtable-part-budget-endgame-14198610.

15. Minsky. Op. cit. 11-15.

16. Ibid. 15. Minsky continues:

“It turns out that the accomplishments of pure theory during the 1950s and 1960s are more apparent than real, when the problems of a financially sophisticated capitalist economy are under consideration.… Thus the purely intellectual pursuit of consistency between what was taken to be an elegant and scientifically valid microeconomics and a presumably crude macroeconomics has turned [o]ut to have been a false pursuit; microeconomics is at least as crude as macroeconomics.”

17. As one of The Straddler’s contributing editors, Gary Peatling, observes:

“I’m wondering if this unreality of neoclassical economics is itself a defense mechanism. Since a really unregulated economy is impossible (and is not even desired by the richest and most powerful vested corporate interests), any failure can be blamed on residual regulation. Hence the tenets are always irrefutable, in the manner of what Karl Popper termed a ‘bad science’ (although Popper might not have identified this). Also I’m reminded of John Ruskin’s comment that political economy was like science of gymnastics devised on the assumption that humans have no skeletons.” (Peatling, Gary. Personal communication. October 25, 2011)

18. Temin. Op. cit.

19. “The Predators’ Boneyard: A Conversation with James Kenneth Galbraith.” The Straddler, springsummer2010. http://www.thestraddler.com/20105/piece2.php

20. Minsky. Op. Cit. 16.

21. A comparatively mild articulation of this defensiveness was on display in a sympathetic 2010 New York Times Magazine profile of “lifelong Democrat” Jamie Dimon, CEO of Chase Bank:

“The executive I encountered was on a mission to reclaim a respected place for his industry, even as he admits that it committed serious mistakes. He was adamant that government officials—he seemed to include President Obama—have been unfairly tarring all bankers indiscriminately. ‘It’s harmful, it’s unfair and it leads to bad policy,’ he told me again and again. It’s a subject that makes him boil, because Dimon’s career has been all about being discriminating—about weighing this or that particular risk, sifting through the merits of this or that loan.” (Lowenstein, Roger. “Jamie Dimon: America’s Least-Hated Banker.” New York Times Dec. 1, 2010. www.nytimes.com/2010/12/05/magazine/05Dimon-t.html)

22. Minsky. Op Cit. 164.

23. Ibid. 163.

24. Ibid. 165.