Embracing Wynne Godley, an Economist Who Modeled the Crisis

By Jonathan Schlefer

The New York Times, September 10, 2013. All rights Reserved.

BOSTON — With the 2008 financial crisis and Great Recession still a raw and painful memory, many economists are asking themselves whether they need the kind of fundamental shift in thinking that occurred during and after the Depression of the 1930s. “We have entered a brave new world,” Olivier Blanchard, the International Monetary Fund’s chief economist, said at a conference in 2011. “The economic crisis has put into question many of our beliefs. We have to accept the intellectual challenge.”

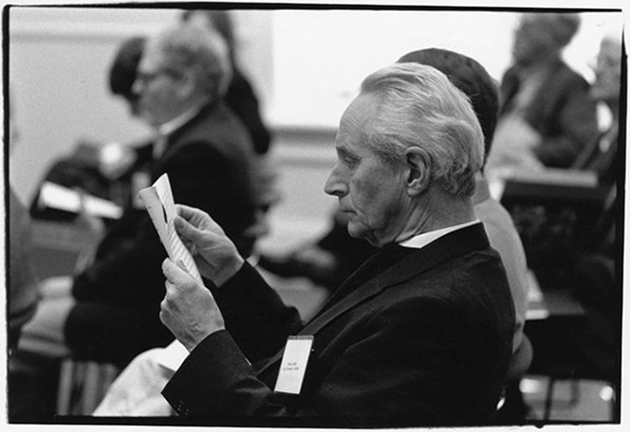

If the economics profession takes on the challenge of reworking the mainstream models that famously failed to predict the crisis, it might well turn to one of the few economists who saw it coming, Wynne Godley of the Levy Economics Institute. Mr. Godley, unfortunately, died at 83 in 2010, perhaps too soon to bask in the credit many feel he deserves.

But his influence has begun to spread. Martin Wolf, the eminent columnist for The Financial Times, and Jan Hatzius, chief economist of global investment research at Goldman Sachs, borrow from his approach. Several groups of economists in North America and Europe — some supported by the Institute for New Economic Thinking established by the financier and philanthropist George Soros after the crisis — are building on his models.

In a 2011 study, Dirk J. Bezemer, of Groningen University in the Netherlands, found a dozen experts who warned publicly about a broad economic threat, explained how debt would drive it, and specified a time frame.

Most, like Nouriel Roubini of New York University, issued warnings in informal notes. But Mr. Godley “was the most scientific in the sense of having a formal model,” Dr. Bezemer said.

It was far from a first for Mr. Godley. In January 2000, the Council of Economic Advisers for President Bill Clinton hailed a still “youthful-looking and vigorous” expansion. That March, Mr. Godley and L. Randall Wray of the University of Missouri-Kansas City derided it, declaring, “Goldilocks is doomed.” Within days, the Nasdaq stock market peaked, heralding the end of the dot-com bubble.

Why does a model matter? It explicitly details an economist’s thinking, Dr. Bezemer says. Other economists can use it. They cannot so easily clone intuition.

Mr. Godley was relatively obscure in the United States. He was better known in his native Britain — The Times of London called him “the most insightful macroeconomic forecaster of his generation” — though often as a renegade.

Mainstream models assume that, as individuals maximize their self-interest, markets move the economy to equilibrium. Booms and busts come from outside forces, like erratic government spending or technological dynamism or stagnation. Banks are at best an afterthought.

The Godley models, by contrast, see banks as central, promoting growth but also posing threats. Households and firms take out loans to build homes or invest in production. But their expectations can go awry, they wind up with excessive debt, and they cut back. Markets themselves drive booms and busts.

Why did Mr. Godley, who had barely any formal economics training, insist on developing a model to inform his judgment? His extraordinary efforts to overcome a troubled childhood may be part of the explanation. Tiago Mata of Cambridge University called his life “a search for his true voice” in the face of “nagging fear that he might disappoint [his] responsibilities.”

Mr. Godley once described his early years as shackled by an “artificial self” that kept him from recognizing his own spontaneous reactions to people and events. His parents separated bitterly. His mother was often away on artistic adventures, and when at home, she spent long hours coddling what she called “my pain” in bed.

Raised by nannies and “a fierce maiden aunt who shook me violently when I cried,” Mr. Godley was sent at age 7 to a prep school he called a “chamber of horrors.”

Despite all that, Mr. Godley, with his extraordinary talent, still managed to achieve worldly success. He graduated from Oxford with a first in philosophy, politics and economics in 1947, studied at the Paris Conservatory, and became principal oboist of the BBC Welsh Orchestra.

But “nightmarish fears of letting everyone down,” he recalled, drove him to take a job as an economist at the Metal Box Company. Moving to the British Treasury in 1956, he rose to become head of short-term forecasting. He was appointed director of the Department of Applied Economics at Cambridge in 1970.

In the early 1980s, the British Tory government, allied with increasingly conventional economists at Cambridge, began “sharpening its knives to stab Wynne,” according to Kumaraswamy Velupillai, a close friend who now teaches at the New School in New York. They killed the policy group he headed and, ultimately, the Department of Applied Economics.

But after warning of a crash of the British pound in 1992 that took official forecasters by surprise, Mr. Godley was appointed to a panel of “six wise men” advising the Treasury.

In 1995 he moved to the Levy Institute outside New York, joining Hyman Minsky, whose “financial instability hypothesis” won recognition during the 2008 crisis.

Marc Lavoie of the University of Ottawa collaborated with Mr. Godley to write “Monetary Economics: An Integrated Approach to Credit, Money, Income, Production and Wealth” in 2006, which turned out to be the most complete account he would publish of his modeling approach.

In mainstream economic models, individuals are supposed to optimize the trade-off between consuming today versus saving for the future, among other things. To do so, they must live in a remarkably predictable world.

Mr. Godley did not see how such optimization is conceivable. There are simply too many unknowns, he theorized.

Instead, Mr. Godley built his economic model around the idea that sectors — households, production firms, banks, the government — largely follow rules of thumb.

For example, firms add a standard profit markup to their costs for labor and other inputs. They try to maintain adequate inventories so they can satisfy demand without accumulating excessive overstock. If sales disappoint and inventories pile up, they correct by cutting back production and laying off workers.

In mainstream models, the economy settles at an equilibrium where supply equals demand. To Mr. Godley, like some Keynesian economists, the economy is demand-driven and less stable than many traditional economists assume.

Instead of supply and demand guiding the economy to equilibrium, adjustments can be abrupt. Borrowing “flows” build up as debt “stocks.”

If rules of thumb suggest to households, firms, or the government that borrowing, debt or other things have gone out of whack, they may cut back. Or banks may cut lending. The high-flying economy falls down.

Mr. Godley and his colleagues expressed just this concern in the mid-2000s. In April 2007, they plugged Congressional Budget Office projections of government spending and healthy growth into their model. For these to be borne out, the model said, household borrowing must reach 14 percent of G.D.P. by 2010.

The authors declared this situation “wildly implausible.” More likely, borrowing would level off, bringing growth “almost to zero.” In repeated papers, they foresaw a looming recession but significantly underestimated its depth.

For all Mr. Godley’s foresight, even economists who are doubtful about traditional economic thinking do not necessarily see the Godley-Lavoie models as providing all the answers. Charles Goodhart of the London School of Economics called them a “gallant failure” in a review. He applauded their realism, especially the way they allowed sectors to make mistakes and correct, rather than assuming that individuals foresee the future. But they are still, he wrote, “insufficient” in crises.

Gennaro Zezza of the University of Cassino in Italy, who collaborated with Mr. Godley on a model of the American economy, concedes that he and his colleagues still need to develop better ways of describing how a financial crisis will spread. But he said the Godley-Lavoie approach already is useful to identify unsustainable processes that precede a crisis.

“If everyone had remained optimistic in 2007, the process could have continued for another one or two or three years,” he said. “But eventually it would have broken down. And in a much more violent way, because debt would have piled up even more.”

Dr. Lavoie says that one of the models he helped develop does make a start at tracing the course of a crisis. It allows for companies to default on loans, eroding banks’ profits and causing them to raise interest rates: “At the very least, we were looking in the right direction.”

This is just the direction that economists building on Mr. Godley’s models are now exploring, incorporating “agents” — distinct types of households, firms and banks, not unlike creatures in a video game — that respond flexibly to economic circumstances. Stephen Kinsella of the University of Limerick, the Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz and Mauro Gallegati of Polytechnic University of Marche in Italy are collaborating on one such effort.

In the meantime, Mr. Godley’s disciples say his record of forecasting still stands out. In 2007 Mr. Godley and Dr. Lavoie published a prescient model of euro zone finances, envisioning three outcomes: soaring interest rates in Southern Europe, huge European Central Bank loans to the region or brutal fiscal cuts. In effect, the euro zone has cycled among those outcomes.

So what do the Godley models predict now? A recent Levy Institute analysis expresses concern not about serious financial imbalances, at least in the United States, but weak global demand. “The main difficulty,” they wrote, “has been in convincing economic leaders of the nature of the main problem: insufficient aggregate demand.” So far, they are not having much success.

A version of this article appears in print on September 11, 2013, on page B1 of the New York edition with the headline: Embracing Economist Who Modeled the Crisis.