That “Vision Thing”: Formulating a Winning Policy Agenda

There are many ways to lose a presidential election, and pundits have come up with a long list: President Biden hung on too long; voters still weren’t ready for a female of color—too many are racist and sexist; too many leftists supported third party candidates. Others offer contradictory views: it’s the voters fault; she was too radical; she was too centrist; she didn’t sufficiently separate herself from Biden; she never clearly stated her position on the war in Gaza; she didn’t give enough press conferences and interviews; and she spent more time campaigning with Cheneys than with presidents of labor unions. While all probably contributed to her loss, more commentators are increasingly pointing to her inability to articulate and sell her vision of the nation she would like to help create. It’s that vision thing, again.[i]

This policy brief assesses the compatibility between a vision of progressive public policy and what might be gleaned from the mood of the electorate. Part of the utility of this exercise is that it gives us a sense of the landscape of opportunities for implementing change. We begin with a quick overview of recent elections and the visions that the winning candidates articulated to win. We then examine why the Democrats lost the presidential election, focusing on analysis of voting patterns and voter sentiment. Finally, we outline a vision that incorporates the popular policies we believe could win an election for a progressive candidate. Our vision is informed by Hyman Minsky’s approach to economic policy, but also by the results of polls indicating that voters are far more progressive than either party gives them credit for. Neither the traditional Reagan Republican vision, nor the post-Reagan Democratic vision is appealing to the majority of today’s voters.

In recent elections, Republicans and Democrats have been competing for the votes of the suburban middle class. The pocketbook issues of the working class have been largely ignored by both parties. This group comprises the true swing voters (voting for Trump in 2016 and 2024 and for Biden in 2020) but their votes are largely protest votes—“throw out the bums” votes—against incumbents who have not delivered for them. We will outline economic policies that could win them over for the next election. To be sure, we do not believe that every “popular” policy is a good policy, but in our assessment, good progressive policies are far more popular with the electorate than is typically recognized by either party. Finally, we are economists and primarily interested in the type of economic policies that would improve the wellbeing of the American working class. We do not aim to outline a specific political strategy for a specific political party.

In the next section, we look at the shifting allegiances of American voters as the Democratic party lost the support of its traditional base and came to be seen as the party of the educated, socially liberal, and relatively economically secure—led largely by a party elite that has too often embraced neoliberalism.

Pavlina R. Tcherneva, President

February 2025

The Surprising Shift of Party Allegiance

Many analysts have closely examined the 2024 results and noted that the Democrats have lost support among their traditional base—lower income, working class, and people of color. However, they have also argued that this is a longer-term trend, and that we can observe similar results in many of the other rich, developed countries. In this section, we summarize the longer-term voting trends in the US. In a later section, we will provide more details on the 2024 election.

Bleeding Electoral Support by Catering to the Comfortable Classes

For the first time since 1960, Democrats earned a greater margin of support among the richest third of American voters than they did among the poorest or middle third in the 2024 elections (Xiao et al.). Support for Democrats among the poorest third has collapsed sharply since 2010, while support among the richest has soared—a result seemingly at odds with the view that the shift is long-term.[ii]

Notably, only the richest third report that their financial situation has improved when compared with a year before, while for the bottom and middle third, prospects are significantly worse (ibid.). Among those earning $50,000 or less, there was a 15-point swing toward Trump, while there was a bigger shift toward Harris among voters earning $100,000 or more. The former were the same voters for whom the threat of unemployment increased (Tooze 2024).

Not surprisingly (since a college degree boosts income), educational attainment follows a similar pattern, so Democrats are also losing the voters with less education: ”In November, 56 percent of voters without college degrees voted for Mr. Trump. In 1992, just 36 percent of voters with only a high school diploma voted Republican—about the same percentage that Barry Goldwater got in his overwhelming defeat against Lyndon Johnson in 1964.” (Weisman 2025)

Most Americans do not go to college, and as costs have exploded, catering to the well-educated and well-paid is not likely to be a winning strategy. For a long time, Democrats have relied on the urban and suburban voter, but they have recently received smaller shares among the large metro counties. For the first time in two decades, the suburban vote also went to the Republicans (Xiao et al.).

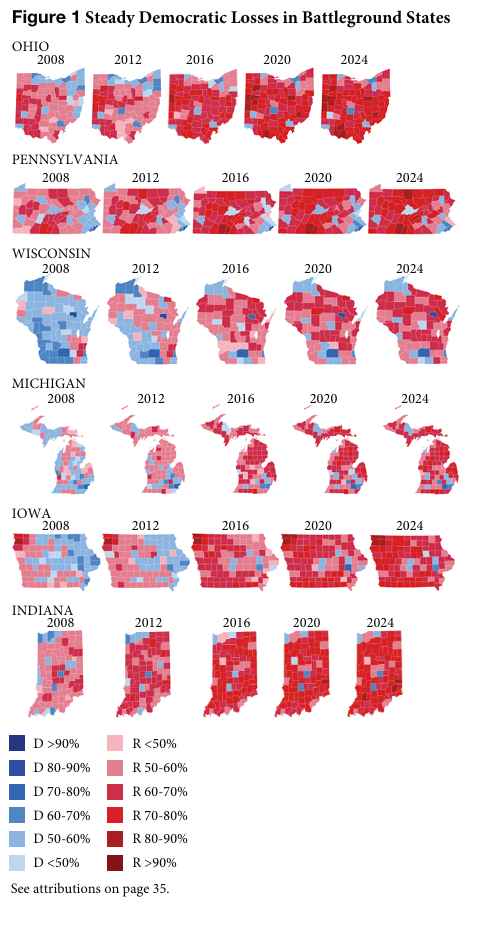

Democrats have been bleeding rural support since the Clinton administration, despite the claim that he presided over a Goldilocks economy and low unemployment. The tale of two Americas may have been drafted during the Reagan years, but it was largely entrenched by the neoliberal policies under Clinton, W. Bush, and Obama. The loss among rural voters has been striking, especially when looking at bellwether races as in OH or PA (which voted for the winning presidential candidate 90 percent and 82 percent of the time since 1980, respectively) and in other competitive states such as WI, MI, IN, and IA (Figure 1). The pattern has been clear since 2008: in every subsequent election, blue counties turned pink, pink counties turned red, and red counties turned deep red.

None of this should suggest that Republicans have an unbeatable strategy. Trump’s win was rather narrow by historical standards (he won the popular vote by the fourth smallest margin since the 1960s). But it does speak to the uninspiring performance of Democrats. Since 2008, not only have Democrats been losing the rural and suburban vote, more significantly, as the Wall Street Journal reports (Kamp et al. 2024), Trump’s sweeping victories took place in counties that are either economically distressed or at risk and in those with predominantly blue-collar jobs that face competition from automation as well as competition from low wages—at home (for example, in the South) and abroad.

According to the Brookings Institute (Muro and Methkupally 2024), 86 percent of all counties in the US voted for Trump in 2024 and yet represented only 38 percent of the nation’s GDP—a pattern that was clearly visible in 2016 and the 2020 elections. Republicans have been making unmistakable gains among poorer and distressed communities (Muro and Methkupally 2024). In 2024, Trump also won in a majority of counties that had not recovered from the pandemic. According to the BEA, 30 million people live in 650 counties that had not restored their pre-pandemic GDP, and 576 of them went for Trump (Donnan, Ahasan, and Tanzi 2025). According to Bloomberg and The Economic Innovation Group, Trump also won overwhelmingly among Americans who heavily depended on government assistance: in 8 out of 10 counties that went for Trump, residents get 40 percent of their collective income in the form of government benefits (Donnan, Ahasan, and Tanzi 2025).

The surprising thing, however, is that those counties benefitted significantly under President Biden’s policies boosting government assistance, but still chose Trump. As Edsall (2025), writes:

In 2020 the 2,548 counties that voted for Trump accounted for 29 percent of gross domestic product, according to Brookings data. In 2024, after four years with Biden and Harris in office, the 2,553 counties that voted for Trump produced 38 percent of the gross domestic product. That nine-point increase in the share of G.D.P. translates into $3.66 trillion worth of additional goods and services produced in Trump-voting counties, according to Brookings—an exceptional economic lift by any standard. In addition, the share of national income going to the Trump counties grew to 43 percent from 34, and the share of private employment rose to 42 percent from 33, according to a separate data set supplied to The Times by Mark Muro, a senior fellow at Brookings.

In other words, while the traditional Democratic base—the low-income voter—had shifted party allegiance toward Trump since his first election, the counties that voted for Trump in 2024 had performed better under Biden’s presidency (probably due to the COVID fiscal relief spending that boosted the government assistance that red counties rely on) but still punished the Democrats. We offer an explanation below. We first turn to a discussion of what we believe to be the most important failure of the Democratic presidential campaign—the absence of a clearly stated vision.

That Vision Thing: A Brief History

When George H. W. Bush lost his re-election bid in 1992, it was attributed to his inability to articulate a clear set of policies. Even his official Senate bio reads “Bush […] suffered from his lack of what he called ‘the vision thing,’ a clarity of ideas and principles that could shape public opinion and influence Congress.” Ironically, Bill Clinton won that election largely by embracing much of President Reagan’s “small government” vision and poaching voters from among traditional Republican groups. According to a New York Times article (Toner 1992), the day after the election: “[t]he President-elect, capping an astonishing political comeback for the Democrats over the last 18 months, ran strongly in all regions of the country and among many groups that were key to the Republicans’ dominance of the 1980’s: Catholics, suburbanites, independents, moderates and the Democrats who crossed party lines in the 1980’s to vote for Ronald Reagan and Mr. Bush.”

Clinton (1992) began his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention, saying “Tonight I want to talk with you about my hope for the future, my faith in the American people, and my vision of the kind of country we can build together.” He forcefully indicted President Bush for his lack of vision:

Of all the things George Bush has ever said that I disagree with, perhaps the thing that bothers me most, is how he derides and degrades the American tradition of seeing and seeking a better future. He mocks it as the “vision thing.”

But just remember what the Scripture says: “Where there is no vision, the people perish.”

I hope—I hope nobody in this great hall tonight, or in our beloved country has to go through tomorrow without a vision. I hope no one ever tries to raise a child without a vision. I hope nobody ever starts a business or plants a crop in the ground without a vision. For where there is no vision, the people perish.

Clinton laid out his vision and his “covenant” with the people, promising to cut government waste and balance the budge—“a new approach to government, a government that offers more empowerment and less entitlement,” and “a government that understands that jobs must come from growth in a vibrant and vital system of free enterprise […] That’s what this New Covenant is all about.”

He went on, detailing the vision thing and its policies. This was not going to be your typical Democratic campaign—the vision was more Reaganesque than the visions of Roosevelt, Kennedy, or Johnson.

Key points included:

We offer our people a new choice based on old values. We offer opportunity. We demand responsibility. We will build an American community again. The choice we offer is not conservative or liberal. In many ways, it’s not even Republican or Democratic. It’s different. It’s new. And it will work. It will work because it is rooted in the vision and the values of the American people.

An America in which the doors of colleges are thrown open once again to the sons and daughters of stenographers and steelworkers. We’ll say: Everybody can borrow the money to go to college. An America in which middle-class incomes, not middle-class taxes, are going up.

An America in which the rich are not soaked, but the middle class is not drowned, either.

An America where we end welfare as we know it.[iii]

By 1994, he added the Clinton Crime Bill with the harsh “three strikes and you’re out” provision. For the most part, Clinton offered Reaganomics glossed with an “I feel your pain” human face.[iv] While recovery was slow (contributing to midterm Democratic party losses in 1994), growth did eventually pick up and Clinton was reelected. He did, indeed, balance the budget but the fiscal headwinds and bursting of the dot.com bubble caused a downturn and George W. Bush narrowly defeated Al Gore in 2000.[v]

President Bush’s vision was quite different—he proposed to create the “Ownership Society.” Privatization of Social Security was at the top of the agenda, but Bush went much further, as Wray (2005) summarized:

Other “reforms” contemplated or already under way include tightening bankruptcy law, replacing income and wealth taxes with consumption taxes, transferring health care burdens to patients, devolution of government responsibility (while relieving state and local governments of the burden of “unfunded mandates”), substituting “personal reemployment and training accounts” for unemployment benefits, “No Child Left Behind” and school vouchers legislation, eliminating welfare “entitlements,” bridling “runaway trial lawyers,” transforming private pensions to defined-contribution plans, the movement against government “takings,” and continuing attempts to hand national resources over to private exploiters. Hence, while Peter H. Wehner (Bush’s director of strategic initiatives) recognizes that privatization of Social Security would “rank as one of the most significant conservative undertakings of modern times,” the neocons have a full plate of other “ownership society” policy proposals.

While President Bush had inherited a troubled economy, unprecedented bubbles in real estate, commodities, and, especially, housing boosted growth. Bush narrowly won reelection in 2004, but the Fed began raising interest rates—probably to prick the bubbles—and the economy collapsed into the Global Financial Crisis.

Barack Obama won the election in 2008 with his “audacity of hope” for a better America. In his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention, he emphasized healthcare, education, and jobs while contrasting his vision with that of the Republicans (trying to pin the pursuit of the “Ownership Society” on candidate John McCain):

In Washington, they call this the Ownership Society, but what it really means is — you’re on your own. Out of work? Tough luck. No health care? The market will fix it. Born into poverty? Pull yourself up by your own bootstraps — even if you don’t have boots. You’re on your own. Well, it’s time for them to own their failure. It’s time for us to change America.

You see, we Democrats have a very different measure of what constitutes progress in this country. We measure progress by how many people can find a job that pays the mortgage; whether you can put a little extra money away at the end of each month so you can someday watch your child receive her college diploma. We measure progress in the 23 million new jobs that were created when Bill Clinton was president — when the average American family saw its income go up $7,500 instead of down $2,000 like it has under George Bush.

We measure the strength of our economy not by the number of billionaires we have or the profits of the Fortune 500, but by whether someone with a good idea can take a risk and start a new business, or whether the waitress who lives on tips can take a day off to look after a sick kid without losing her job — an economy that honors the dignity of work. The fundamentals we use to measure economic strength are whether we are living up to that fundamental promise that has made this country great — a promise that is the only reason I am standing here tonight….

What is that promise? It’s a promise that says each of us has the freedom to make of our own lives what we will, but that we also have the obligation to treat each other with dignity and respect. It’s a promise that says the market should reward drive and innovation and generate growth, but that businesses should live up to their responsibilities to create American jobs, look out for American workers, and play by the rules of the road.

Ours is a promise that says government cannot solve all our problems, but what it should do is that which we cannot do for ourselves — protect us from harm and provide every child a decent education; keep our water clean and our toys safe; invest in new schools and new roads and new science and technology.

Our government should work for us, not against us. It should help us, not hurt us. It should ensure opportunity not just for those with the most money and influence, but for every American who’s willing to work.

That’s the promise of America — the idea that we are responsible for ourselves, but that we also rise or fall as one nation; the fundamental belief that I am my brother’s keeper; I am my sister’s keeper. That’s the promise we need to keep. That’s the change we need right now.

Note also that he attributed his view to Democrats—“we Democrats,” not “I,” will change America. It was a winning strategy in 2008. Unfortunately, the Global Financial Crisis worsened and attention immediately turned to saving Wall Street. Main Street only got $800 billion of relief (spread over two years[vi]) while Congress allocated another $800 billion to the Treasury to save banks. By contrast, the Fed spent and lent over $29 trillion to save the global financial system.[vii] The recovery was very slow and virtually all the gains went to the tippy-top of the income distribution (Tcherneva 2015).

However, Obama was able to win reelection thanks, in large part, to the Republican Party’s choice of a Romney–Ryan ticket that the Democrats were able to paint as plutocratic and out-of-touch with the American people. Romney cemented that impression by labeling 47 percent of the population as irresponsible takers who pay no income taxes:

There are 47 percent of the people who will vote for the president no matter what. All right, there are 47 percent who are with him, who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it—that that’s an entitlement. And the government should give it to them. And they will vote for this president no matter what. … These are people who pay no income tax. … [M]y job is not to worry about those people. I’ll never convince them they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives. (Madison 2012)[viii]

As we discussed above (also see Figure 1), in spite of Obama’s reelection, there were already clear warning signs in 2012 that the Democrats were losing rural and working-class support—a topic we return to later.

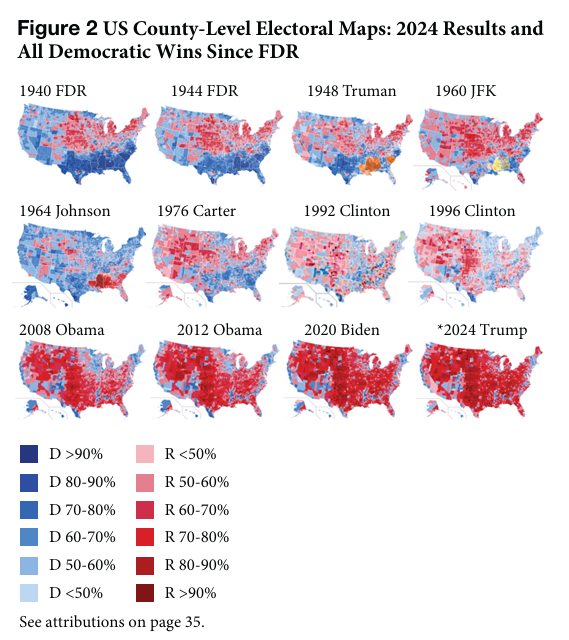

Whatever vision the Democrats offered, none matched that put forward by FDR. When examining the county-level voting patterns during general elections when Democrats won (plus 2024, when they lost), each subsequent win after FDR/Truman happened with an increasingly smaller and smaller share of counties across America. The shift is striking when looking at the percentage of the vote Democrats earned in those counties. JFK lost large swaths of the Midwest. Johnson was able to regain some of these losses, in large part because of his vision for a Great Society, though his commitment to civil rights likely lost him the deep South. Carter lost the Midwest again but won over the South, and Clinton’s popularity was more evenly spread across the country, though he did not do as well in his reelection.

By 2008, middle America, the Midwest, and the South, no longer voted for Democrats. President Obama was elected largely because of the urban vote, though he did well in some rural counties—especially in the Rust Belt. As Figure 1 showed above, he had lost much of that support by the 2012 election, losses which continued across the nation during the Biden and Harris campaigns. The electoral map had turned red. Urban voters remained the sole Democratic constituency. These highly populated areas were enough to hand Obama and Biden their victories, but the rest of the country had decidedly turned against the Democrats. The forgotten rural voter, the downwardly mobile communities, the Rust Belt, Corn Belt, and Bible Belt—all swung far to the right, more than in any other time after Clinton’s elections. The working families in suburban areas, too, are getting cold feet—and turning red. Across the nation, as the losses deepened, Democrats lost by a larger and larger share of the vote across many counties (Figure 2).

Elections in the Trump Era

We will be brief on the 2016 and 2020 elections of Presidents Trump and Biden. The 2016 election cycle featured Bernie Sanders, who had a clear pro–working class agenda, facing Hillary Clinton—who did not. On the eve of the Democratic National Convention, in July 2016, PBS News Hour had announced it was Hillary’s turn now to make her case to serve as president—and “her turn” became a meme that was picked up by supporters and critics alike (Pace and Furlow 2016).[ix] Vice President Biden dropped out of the race early, helping Clinton to secure the support of the elite wing of the party—the highly educated, middle-to-high income, urban and professional class that increasingly abandoned the Republican party in favor of the cultural values expressed by Democrats. Like Romney, Clinton had her own gaffes—insulting Trump supporters as “deplorables,” and had earlier, as First Lady, referred to young Black men as “super predators” (Reilly 2016).[x]

However, during her campaign she focused on policy benefitting families, strengthening Obamacare, gender equality (breaking the glass ceiling), LGBT rights, and—especially—Donald Trump. Her campaign theme was “stronger together,” apparently based on her book, It Takes a Village. In a comprehensive analysis, reporters Allen and Parnes attributed Clinton’s loss to her lack of vision, inability to inspire voters, prioritization of turning out voters thought to be leaning toward her, and her insistence on loyalty over competency. Summing up the arguments of the book, Thomas Goulding (2017) wrote:

For all the strategic and structural faults of the campaign, the lack of vision or platform from the candidate herself was a particularly jarring theme. When Hillary announced her decision to run, it wasn’t immensely clear to many of her aides, let alone the public, “why her, and why now.”

Clinton’s aimlessness was typified by her Roosevelt Island speech formally announcing her candidacy in the summer of 2015, when she “whimpered her way into the election.” The speech contained “no overarching narrative explaining her candidacy, no framing of Hillary as the point of an underdog spear, no emotive power.”

To her critics, including many Sanders supporters, this betrayed a Clintonian entitlement to power, without having to convince the electorate of quite what made her the best person to shape America’s future. “America can’t succeed unless you succeed. That is why I am running for president of the United States of America,” she pronounced in that speech, in a “trite tautology” that did as little to strike a chord with an electorate as her campaign slogan “Stronger Together.”

This was an electorate that had lost huge amounts of faith in political and economic institutions, and in addition to the danger of fielding a candidate that embodies the establishment so thoroughly as Clinton, it was often hard for voters to name a concrete policy or change that Clinton was proposing.

Despite Clinton being a self-professed policy wonk, who “lives for the complexity,” she “didn’t like taking issues she’d been working on for years and boiling them down into little sound bites.” As a result, chief speechwriter Dan Schwerin complained repeatedly that Hillary was not doing enough to find a vision of her own that he could help her put into words. “More than a year into the campaign, her staff didn’t know her well enough to turn her candidacy into a compelling narrative for her.”

All of this may sound quite familiar—as candidate Harris was criticized along similar lines (with the notable exception that she was known as a prosecutor, not a policy wonk). Clinton (like Harris, as discussed in the next section) performed much worse in the swing states, including those in which polls seemed to indicate that she would win.

After Trump won the election, the economy did perform reasonably well—not surprising given that it was finally shaking off the debt overhang left by the Global Financial Crisis. However, with the COVID pandemic and response widely characterized as bungled, Trump and the Republicans lost in 2020 (and again—surprisingly—in the midterms of 2022). Biden’s campaign emphasized healthcare, tuition-free colleges, the environment, abortion, and equal rights. While those are associated with liberal positions, they are not targeted at working class voters. Sanders (again) appealed to young and working-class voters, but Biden came to be seen as the candidate most likely to defeat Trump.[xi]

In his acceptance speech at the Democratic convention, Biden (2020) contrasted his own approach with the dark vision of Trump:

If you entrust me with the presidency, I will draw on the best of us, not the worst. I will be an ally of the light, not the darkness. It is time for us, for we, the people, to come together. And make no mistake, united we can and will overcome this season of darkness in America….

This campaign isn’t just about winning votes. It’s about winning the heart and, yes, the soul of America—winning it for the generous among us, not the selfish. Winning it for workers who keep this country going, not just the privileged few at the time.

He went on to criticize Trump and his handling of the pandemic, promising to tackle it immediately before moving on to his longer-term plans:

[M]y economic plan is all about jobs, dignity, respect, and community. Together, we can and will rebuild our economy. And when we do, we’ll not only build back, we’ll build back better. With modern roads, bridges, highways, broadband, ports and airports as a new foundation for economic growth, with pipes that transport clean water to every community, with 5 million new manufacturing and technology jobs so the future is made in America, with a health care system that lowers premiums, deductibles, drug prices—by building on the affordable care act he’s trying to rip away—with an education system that trains our people for the best jobs of the 21st century. There’s not a single thing American workers can’t do, and where cost doesn’t prevent young people from going to college and student debt doesn’t crush them when they get out, with a child care and elder care system that makes it possible for parents to go to work and for the elderly to stay in their homes with dignity, with an immigration system that powers our economy and reflects our values, and with newly empowered labor unions. They’re the ones that built the middle class. With equal pay for women, with rising wages you can raise a child on, a family on. And yes, we’re going to do more than praise our essential workers. We’re finally going to pay them. Pay them.

We can and we will deal with climate change. It’s not only a crisis, it’s an enormous opportunity, an opportunity for America to lead the world in clean energy and create millions of new good paying jobs in the process.

“Build Back Better” (BBB) was his vision, and—arguably—that is what he pursued as president, with some success.[xii] But any success achieved was tainted by inflation. We will not pursue that issue here, but since the inflation was a global phenomenon, his policies did not deserve much blame.[xiii] But, as we discuss below, by 2022, Biden had started backtracking on his BBB vision in favor of deficit reduction. As many pundits have proclaimed, incumbents are blamed for economic problems and he had an uphill battle for the 2024 election—against a revitalized Trump. While Biden insisted that he remained the candidate most likely to defeat Trump, it became increasingly evident that he was not up to the task. Vice President Harris was anointed without a primary.

In her Democratic convention acceptance speech (Sarnoff 2024), Harris talked about her mother and her experience as a prosecutor, emphasizing that “[e]very day in the courtroom, I stood proudly before a judge and said five words: ‘Kamala Harris, for the People’.” She promised to be president for all the people. She talked about the dangers of another Trump presidency presumably trying to implement “Project 2025,” and the possibility that Americans would lose much of the social safety net they rely upon. She promised to help the middle class:

We are charting a new way forward. Forward—to a future with a strong and growing middle class. Because we know a strong middle class has always been critical to America’s success. And building that middle class will be a defining goal of my presidency. This is personal for me. The middle class is where I come from.

She promised “we will create what I call an ‘opportunity economy’… where everyone has a chance to compete” (emphasis added). She went on:

As President, I will bring together labor and workers, small business owners and entrepreneurs and American companies to create jobs, grow our economy and lower the cost of everyday needs—like health care, housing and groceries.

We will provide access to capital for small business owners, entrepreneurs, and founders. We will end America’s housing shortage and protect Social Security and Medicare.

[I]nstead of a Trump tax hike, we will pass a middle-class tax cut that will benefit more than 100 million Americans.

In the rest of the speech, she highlighted her support for social issues important to many liberal voters—reproductive rights and an ability to make decisions about what she called “matters of heart and home” and “fundamental freedoms”:

The freedom to live safe from gun violence—in our schools, communities, and places of worship—the freedom to love who you love openly and with pride. The freedom to breathe clean air, drink clean water, and live free from the pollution that fuels the climate crisis. And the freedom that unlocks all the others: the freedom to vote.

She went on to warn about Trump’s plans for immigrants, and for NATO and Ukraine, as well as his propensity to befriend tyrants. By contrast, she promised, “[a]s Commander-in-Chief, I will ensure America always has the strongest, most lethal fighting force in the world.” She doubled down on support for both Ukraine and Israel, although she did say that “President Biden and I are working around the clock because now is the time to get a hostage deal and cease-fire done.”

As she neared the end of her speech, she summed it up this way: “Let us show each other—and the world—who we are and what we stand for. Freedom. Opportunity. Compassion. Dignity. Fairness. And endless possibilities.”

While she covered a lot of topics, it is difficult to identify a clear statement of her economic vision—other than to build an “opportunity economy” to enable people to “compete.” And over the course of her campaign, she did not make that clearer.

Out of office, Trump retained his campaign staff (an unprecedented action) and prepared for the next election; in anticipation, his supporters put together Project 2025 (supervised by the Heritage Foundation) to guide his next term in office. But once the contents were revealed, Trump quickly disowned it, as reported by Homans (2024):

In July, as the Democrats’ attacks began gaining traction, he took to Truth Social to insist that “I know nothing about Project 2025. I have no idea who is behind it.” (He had, in fact, sat next to Roberts on a 45-minute private flight to a 2022 Heritage conference, where Trump had given a speech praising the organization’s work “to lay the groundwork and detail plans for exactly what our movement will do.”)

The disavowal put Heritage in a bind, and the organization scrambled to batten down the hatches. The think tank quickly fired Paul Dans, Project 2025’s director. In addition to delaying the release of the book, Roberts’s publisher, Broadside Books, scrapped its original subtitle (“Burning Down Washington to Save America”) and cover art (which featured a charred match).

After Trump won, though, Roberts was brought back into the fold, and once Trump began to announce his appointments, Roberts crowed: “If you look at these appointments, I mean, 100 percent of them are friends of Heritage.”

Over the course of the campaign, Trump doubled down on his dystopian view of the state of America. His claims (Atlantic 2024) included:

Our country is being lost. We’re a failing nation.

If she’s president, I believe that Israel will not exist within two years from now.

We’re playing with World War III and we have a president that we don’t even know if he’s—where is our president?

We’re a failing nation. We’re a nation that’s in serious decline.

This is the most divisive presidency in the history of our country. There’s never been anything like it. They’re destroying our country.

He repeatedly claimed immigrants are eating our pets—even after he was told that it wasn’t true. He claimed that Aurora, Colorado—ironically, a well-run city led by a Republican mayor—had been taken over by murderous gangs and promised to liberate it when elected. As the Denver Post reported[xiv] after the election:

President-elect Donald Trump has relentlessly tried to paint the city of 386,000 people as a violent hell-hole needing drastic federal action to save it from the scourge of illegal immigration. In a clear nod to the white supremacists backing his campaign, Trump repeatedly said recent migrants were “poisoning the blood” of America by flooding across our borders from around the world. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Instead of correcting himself, Trump pledged to “use the Alien Enemies Act of 1789 to bypass due process and round up suspected foreign-born gang members, detain them, and quickly deport them. Trump dubbed his plan ‘Operation Aurora’.” The Post reports that the city was already successfully dealing with the relatively small number of gang members and their crimes and would be “devastated” by such a policy.

Trump’s vision, as articulated during the campaign, was dark. America’s cities are hell-holes and its leaders are evil. A significant proportion of the Republicans in Congress agree—they want disruption and they plan to enable him. And they believe that is what the electorate expects. Trump “was elected to turn this place upside down,” Senator Roger Marshall of Kansas said (The Morning 2024). Trump ran against Washington, against “woke” liberalism, against the mainstream media, against immigration, against Muslims—in short, against things the Democrat’s elite wing might represent. This ensured that he and his positions would be the main topic of conversation for the year leading up to the election. His vision—if one could call it that—was to “Make America Great Again,” leaving it up to individuals to decide what that might look like.[xv] After four decades of stagnating real average wages, that sounded good to many voters and Trump ran a successful “us versus them” campaign.

Note that Reagan and Bill Clinton ran against Washington too, but with positive views of the country. In his acceptance speech at the Republican convention, Reagan (1980) criticized Carter and the Democrats, but went on to say,

More than anything else, I want my candidacy to unify our country; to renew the American spirit and sense of purpose. I want to carry our message to every American, regardless of party affiliation, who is a member of this community of shared values.

And, unlike President Trump, Reagan rejected the notion that he could save America:

Trust me government asks that we concentrate our hopes and dreams on one man; that we trust him to do what’s best for us. My view of government places trust not in one person or one party, but in those values that transcend persons and parties. The trust is where it belongs in the people…. Tonight, let us dedicate ourselves to renewing the American Compact. I ask you not simply to trust me, but to trust your values, our values and to hold me responsible for living up to them. I ask you to trust that American spirit which knows no ethnic, religious, social, political, regional or economic boundaries; the spirit that burned with zeal in the hearts of millions of immigrants from every corner of the earth who came here in search of freedom.

Bill Clinton (1992) also promised that “[w]e will build an American community again. The choice we offer is not conservative or liberal…. It will work because it is rooted in the vision and the values of the American people.” By contrast, Trump has insisted that he “alone can fix it” (Marcus 2018), that he will be a dictator (only) on Day 1,[xvi] that he was anointed by God, that it was a miracle that saved him from assassination (Lutz 2024), and that “[when] somebody’s the president of the United States, the authority is total. And that’s how it’s got to be” (Tackett 2020). He does not limit his attacks to Democrats, either:

Mr Trump told the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) that Americans were “in an epic struggle to rescue our country from the people who hate it and want to absolutely destroy it.” “We had a Republican Party that was ruled by freaks, neocons, globalists, open border zealots and fools,” he said, singling out multiple luminaries of the traditional party by name. “In 2016, I declared: I am your voice. Today, I add: I am your warrior. I am your justice. And for those who have been wronged and betrayed: I am your retribution,” Mr Trump said. “I will totally obliterate the deep state. I will fire the unelected bureaucrats and shadow forces who have weaponized our justice system. And I will put the people back in charge of this country again.” (SBS News 2023)

In the next section, we look at the Harris’ 2024 election loss in detail, before turning to formulate an economic vision that could win.[xvii]

Election 2024 Vision in the Rearview Mirror

Despite hopeful polling and thinking, candidate Harris lost all the swing states and performed worse across most of the country (and with many demographic groups) than President Biden had in 2020. While there were many factors, some listed above, that could have played a role, we focus, here, on the vision. What was lacking? We agree with the assessments of Bernie Sanders (2024), David Sirota (2024), Jeet Heer (2024), Thomas Edsall (2024), Larry Elliot (2024), and Adam Tooze (2024), that her relatively poor performance on election day can be at least partially attributed to the absence of a vision that included policies to address the dire economic situation of lower wage workers and others in the bottom third or half of the income distribution. Sanders, in particular, has harshly blamed the party for abandoning the working class (CNN 2024). He insisted that this was a Democratic Party loss, not only a Kamala Harris loss:

It’s not just Kamala. It’s a Democratic Party which increasingly has become a party of identity politics, rather than understanding that the vast majority of people in this country are working class. This trend of workers leaving the Democratic Party started with whites, and it has accelerated to Latinos and Blacks. Whether or not the Democratic Party has the capability, given who funds it and its dependency on well-paid consultants, whether it has the capability of transforming itself, remains to be seen. (Epstein, Lerer, and Nehamas 2024)

The data seem to back him up, although to some extent, we rely on incomplete counting of ballots as well as on the veracity of exit polls to determine shifts of voters by income and other characteristics. Furthermore, there are the eligible voters who did not cast votes for either candidate—it is not possible to know for certain why they abstained. So, the following analysis of voting needs to be taken with a grain of salt.

Immediately after the election, there were many reports that Harris lost votes among the working class, and particularly significant was the loss among Latino and Black men. Nationally, counties with a Latino majority shifted by 10 percent toward Trump (compared to 2020).

The losses among Latinos is nothing short of catastrophic for the party,” said Representative Ritchie Torres, an Afro-Latino Democrat whose Bronx-based district is heavily Hispanic. Mr. Torres worried that Democrats were increasingly captive to “a college-educated far left that is in danger of causing us to fall out of touch with working-class voters.” (Bender et al. 2023)

In an interview, Sirota argues that Democrats made a mistake by thinking that the swing voter they could flip was a disaffected Republican. While that might have worked in 2020, the math did not work in 2024, especially in a downwardly mobile economy. The real swing voters were the working class—not suburbanite whites. Tooze presents data showing that, in the 2024 election, there was a 15-point swing to Trump by the lowest third of income earners (i.e., those earning below $50,000 annually) compared with 2020. (Note that the federal poverty line for a family of four is currently $31,200[xviii]—so this group includes individuals and families who are struggling.) In post-voting surveys, these voters said they were worried about losing their jobs (more than 18 percent of the group). Trump outscored Harris by 80 to 20 percent among voters who said the economy was their number one issue. By contrast, Harris voters cared about, in descending order of importance, the state of democracy, abortion, foreign policy, the economy, and immigration—and as discussed earlier, democracy, abortion, and immigration were the issues Harris emphasized. Harris got the voters she spoke to, but lost the traditional working-class voters who are struggling economically.

As Times reporter Jennifer Medina (2024) put it: “The working-class voters Vice President Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign needed were not moved by talk of joy. They were too angry about feeling broke.” Medina goes on:

For decades, Democrats had been the party of labor and of the working class, the choice for voters who looked to government to increase the minimum wage or provide a safety net for the poor, the old and the sick. But this year’s election results show how thoroughly that idea has collapsed even among Latino, Black and Asian American voters who had stuck by the party through Donald J. Trump’s first term.

Medina (2024) reports that a poll showed that two-thirds of Trump voters had to cut back on groceries this past year, versus only a third of Harris voters. While Democrats still won among people of color, even those traditional voters had lost trust in the party: “many nonwhite working-class voters said they had come to see the Democratic Party as condescending, overly focused on issues irrelevant to their day-to-day lives”—and, thus, too concerned with social issues. The party showed insufficient concern with economic challenges such as rent and house prices.

A post-election YouGov poll asked working-class voters (defined as those without college degrees) a series of questions, finding that they had shifted significantly toward the Republican party, as reported by Edsall (2025):

Asked which party they trusted “more to improve the economy, protect Americans from crime, handle the issue of immigration,” majorities of respondents chose the Republican Party, ranging from 55 to 34 percent on the economy to 57 to 29 percent on immigration.

Asked whether the Democratic Party or the Republican Party was “in touch or out of touch” and “strong or weak,” majorities of working-class voters described the Democrats as out of touch (53 to 34 percent) and weak (50 to 32) and the Republicans as “in touch” (52 to 35) and “strong” (63 to 23).

More significant, on two survey questions that previously favored Democrats — whether the party is “on my side or not” and which party respondents trusted “to fight for people like me” — the Democrats lost ground to Republicans. Fifty percent of voters participating in the survey said that the Republican Party would fight for people “like me,” while 36 percent said the Democratic Party would. Thirty-four percent of those polled said that the Democratic Party was on their side, and 49 percent said it was not. Fifty percent said that the Republican Party was on their side, and 37 percent said it was not.

Similarly, Greenberg (2024) argues that “Donald Trump won the 2024 election because he was the change candidate who championed working-class discontent.” But, like others, he insists this was not the fault of Harris because, “[f]rom the moment Joe Biden took office, the great working-class majority grew desperate with spiking prices, the safety of their neighborhoods, and government listening to the biggest corporations and elites and neglecting the concerns of working people.” While Biden had provided needed relief from the COVID recession early in his term, inflation and immigration eroded support for him. Greenberg reveals that, during Biden’s campaign, he shared these concerns “with the president, where possible, his White House and campaign teams, and then others on the vice president’s team. I don’t believe Biden’s campaign team served him or the country well.” Instead, both the Biden campaign and then the Harris campaign turned away from the core issues of inflation and immigration. By contrast, Trump focused like a laser on both issues, indeed, linked the two as he, according to Greenberg, “made immigrants the reason for the prohibitive cost of living in housing and other goods, as well as why federal agencies dealing with natural disasters were broke.”

Greenberg (2024) believes Democrats had an opening because voters saw greedy corporations and high profits as the cause of inflation. But instead of a clear message, they chose to claim that the economy was great, thanks to Bidenomics. To no avail, Greenberg wrote to Biden’s campaign: “There is a reason why his approval is stuck. He’s trying to convince people this is a good economy and it is anything but.” In retrospect, he believes “[t]he candidate with the best chance of winning would have been strong on taking on big corporations and bringing down prices most of all, while advancing credible positions on crime, respect for police, the border, and woke policies.” To win in the future, “they will have to proclaim that they authentically understand what ordinary Americans are going through.”

The national rightward shift is a continuation of voting patterns seen in the last two elections. Even in his 2020 defeat, Mr. Trump found new voters across the country. (Both parties earned more votes in 2020 than in 2016.) And although Democrats outperformed expectations in 2022, when some had predicted a “red wave,” they lost many voters who were dissatisfied with rising prices, pandemic-era restrictions and immigration policy.

Some have argued that the mistake Democrats made was to soften the party’s progressive stance on the economy to woo suburban Republicans who were put off by Trump’s behavior, costing Harris the working-class voters she needed.

“They shied away from the populist economic stuff, which they thought would turn off those voters,” said Mike Lux, a longtime Democratic strategist who has spent years studying blue-collar workers. “That was a real mistake. Because it made all of those folks back in Bethlehem and Scranton and Erie think, ‘Well, I guess they really don’t care about me very much.’” (Glueck 2024)

With most of the votes counted, Harris seemed to have improved somewhat over Biden’s performance in some suburban areas but lost too many votes in other areas. Harris garnered about 7.1 million votes less than Biden received in 2020, while Trump increased his total by 2.5 million (Wu et al. 2024).[xix] Democratic voters were not excited and failed to show up to vote:

Larry Sabato, the director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia, acknowledged that Biden voters who swung toward Mr. Trump played a part in Ms. Harris’s loss, but pointed to low Democratic turnout as the larger factor. “They just weren’t excited,” Mr. Sabato said of Democratic voters. “They were probably disillusioned by inflation, maybe the border. And they didn’t have the motivation to get up and go out to vote.”

Pre-election polls showed minority voters swinging toward Mr. Trump, and he appeared to make gains with those groups. He picked up votes in majority-Hispanic counties and in Black neighborhoods of major cities, a preliminary analysis of precinct data shows. But he lost votes, as did Ms. Harris, in majority-Black counties, especially those in the South where turnout dropped overall. (Wu et al. 2024)

According to data supplied by Tooze (2024), Harris voters were more likely to be highly educated—for the first time ever a majority of college-educated whites voted for the Democratic candidate. White women increased their support for the Democratic candidate to a 16 percent margin over the Republican candidate. However, white women without a degree went for Trump by a 27–28 percent margin in the last three elections. Black women consistently supported the Democratic candidate by a wide margin in all three elections, with education level playing no role.[xx] [xxi]

Trump lost vote share this election in counties with more white- than blue-collar workers but gained in counties with more blue-collar workers. He also gained more in counties rated as distressed—and gained less in prosperous counties. Since 1960, Democrats typically beat the Republicans in attracting votes from the poorest third by an average of about a 20 percent margin; in 2024, that margin fell to zero (Tooze 2024). As we have shown above, over the period since 1960, the Democrats had typically lost the vote of the richest third by about a 20 percent margin in elections; in 2024 they won the high-income vote by a 7 percent margin. Democrats continue to lose votes in rural counties by a huge and growing margin, but still win in metropolitan counties by a big margin, while now just breaking even in suburban counties.

The overall message from Tooze is that, despite the Democratic focus on inequality, the party fails to reach the disadvantaged with their message. He characterized the Harris campaign as aristocratic[xxii]—that is, moving toward the center, bringing in affluent college-educated voters. However, he also notes (as do many others) that incumbents are losing all over the high-income world—indeed, Harris’s election was very much closer than elections in most other countries, where incumbents lost by double digits. This seems to indicate a general dissatisfaction with economic performance, regardless of party and regardless of country. From this perspective the Harris result does not stand out at all—it would have been more surprising if she had won. Voters are not happy—especially with economic performance.

In a thoughtful piece, Elliott (2024, cited above) writes in his final editorial for The Guardian that the neoliberal experiment that is now nearly a half-century old has failed—the free-market ideas have universally failed: privatization, deregulation, tax cuts to foment “trickle down” growth, shrinking government, curbing unions, and dismantling capital controls have all boosted wealth at the top and turned the economies into casinos where financial speculation dominates. Until the great inflation, zombie capitalism was driven by extremely low interest rates that boosted speculative fever. Unfortunately, so far, the left has no answer—they recommend that voters stop smoking, drink less, and stop being bigots—allowing so-called populists to remain in power. Moreover, the world’s center of power has moved east and south, while globalization has gone into reverse. Activist industrial policies are now in vogue—and may offer some hope.

Heer (2024) asks, why do Democrats react so strongly in opposition to Bernie Sanders? Because he is bad for the (new) high income base of the party. Heer notes that Pelosi rejects the claim that the party has left the working class behind, but, as Sanders says, during Biden’s term, the Democrats did not even bring forth a bill that would raise the minimum wage to the floor of Congress (a job at the current ridiculously-low minimum wage of $7.25/hour generates a full-time annual income of less than half of the national poverty line for a family of four). Harris, and the Democrats, insisted that the economy was (and is) good, while 60 percent of Americans say it is bad. Effectively, Democrats are saying “I don’t feel your pain”—the opposite of Bill Clinton’s nostrum. (Senator Schumer famously proclaimed that it was fine to lose working class votes by tacking right: “For every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia, and you can repeat that in Ohio and Illinois and Wisconsin.” Obviously, his math was wrong.)[xxiii] According to Winant (2024),

By the middle of his term, Biden had become a de facto austerity president, overseeing the lapse of welfare state expansions, including not just the loss of the child tax credit and temporary cash relief but the retrenchment of SNAP and the booting of millions off Medicaid, all during a period of unified Democratic control. Gradually, Biden largely dropped the demand for progressive social policy and focused his fiscal discussions instead on the deficit—a repetition of the same posture that had condemned the Obama administration and created the opportunity for the rise of Trump in the first place. Emblematizing this capitulation, Biden decided to cave to corporate wishes for the pandemic to be over as a matter of public policy—particularly public policy that enhanced workers’ labor market power—even as it continued to rip through Americans’ lives. In place of earlier progressive ambitions, Biden offered an economic nationalism more or less borrowed from Trump and a new Cold War liberalism. Imagine if, instead of the Second New Deal, Franklin D. Roosevelt had sought reelection by campaigning on a weapons gap, like John F. Kennedy later would.

In 2023, Ro Khanna asked on social media whether the Democratic challenge is the absence of a “compelling economic vision” (Cohn 2023). Shortly after the election, a Times analysis of the results by Epstein, Lerer, and Nehamas concluded:

They lost the White House, surrendered control of the Senate and appeared headed to defeat in the House. They performed worse than four years ago in cities and suburbs, rural towns and college towns. An early New York Times analysis of the results found the vast majority of the nation’s more than 3,100 counties swinging rightward since President Biden won in 2020.

The results showed that the Harris campaign, and Democrats more broadly, had failed to find an effective message against Mr. Trump and his down-ballot allies or to address voters’ unhappiness about the direction of the nation under Mr. Biden. The issues the party chose to emphasize—abortion rights and the protection of democracy—did not resonate as much as the economy and immigration, which Americans often highlighted as among their most pressing concerns. (Epstein, Lerer, and Nehamas 2024)

To conclude this section, the common theme in both the pre- and post-election analyses is that Democrats had neither delivered on nor even highlighted the changes that many voters wanted: policies that would provide economic benefits. They were tired of inflation that reduced purchasing power, wages that remained too low (even in supposedly good labor markets) to support their families, and many other issues related to economic precarity, including the costs of healthcare, prescription drugs, childcare and—for a significant portion of the population—college costs. Even the immigration issue was related to problems of economic precarity—for the immigrants themselves (rising homelessness), for local government (costs of dealing with the unhoused—including immigrants), and the possible deflationary impacts on wages. While the US is a nation of immigrants, each wave of immigration has generated the fear—and sometimes the reality—that wage competition would be detrimental to the living standards of workers. Voters wanted the Democrats to address these issues. In the next section we examine a strategy to address these concerns.

Pocketbook Economics

In recent years, red states have voted for worker-friendly measures commonly associated with the democratic left. At the same time, Democrats who ran on a progressive platform in 2024 won or kept their seats in elections where enthusiasm for the Democratic party fell across demographic subgroups. As Luke Goldstein (2024) documents, moderate Democrats who ran on fighting corporate power, reinforcing antitrust laws, and regulating price increases—policies typically vilified as fringe left—did exceedingly well compared to the national ticket. These moderate Democrats won reelection in deep-red states, outperformed Harris by wide margins in blue states, and beat incumbent corporate democrats. Even those who narrowly lost but campaigned against rampant wealth inequality and broke with market fundamentalism snatched more votes than Harris in their respective districts. Pocketbook issues are not easily painted as “socialism” and continue to resonate with voters of different political stripes.

In this section, we assess the evidence that demonstrates majority support for pocketbook issues and identify the policies that could win elections.

Lessons from the COVID Pandemic

The pandemic was an opportunity for Democrats to recommit to working-class issues. The American Rescue Plan of 2021 (passed without a single Republican vote) extended many of the provisions of the bipartisan CARES act of 2020 and brought a form of economic security that most Americans had not experienced during their lifetimes. With the expansion of Medicare, suddenly healthcare was more affordable, COVID tests were free, telehealth was widely accessible, and workers who lost their employer-provided insurance received 100 percent federal COBRA subsidies. Food assistance was widely available: WIC (the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) was expanded, as were free school meals program and SNAP benefits. Unemployment insurance became more generous as the government topped off state benefits and extended them to new classes of workers not previously covered. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credits (CTC) were expanded dramatically, slashing child poverty rates. Families received a reprieve from the student loan repayment moratorium and the ban on evictions and foreclosures. And while we do not believe that all of these specific programs should be made permanent, they provided a much-needed respite to low-income families and should have informed Democratic policy strategy and messaging. However, as the programs expired, states began removing millions from Medicare rolls and imposing work requirements, causing child poverty to spike—rising higher in 2023 than it had been before the pandemic in 2019.[xxiv]

Meanwhile, as Semler (2024) documents, Biden’s political rhetoric shifted away from Building Back Better (BBB) to deficit and debt reductions. The goal of BBB was to make many of the temporary social safety nets permanent. With the political failure of BBB, however, Biden abandoned championing the very progressive policies that resonated with the public (free education, direct assistance to children and families, early childhood education, paid leave, etc.). Two Democratic holdouts refused to vote for BBB: Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin—the latter being the deciding vote against Biden’s sweeping environmental and social agenda. Manchin—a frequent thorn in the Democratic Party’s side—subsequently retired, but the mistake that Democrats made was to declare defeat. Instead of defending the vision and mission of BBB, Biden backtracked. As per a communique obtained by the American Prospect, the White House instructed administration officials to remove any mention of BBB in the domestic agenda and instead rebrand it as “the values-driven, high-standard, transparent, and catalytic infrastructure initiative.” This ambiguous language also upended Biden’s foreign policy objective of positioning the US clearly as an international leader on climate and social economic policies (Ahlman 2022). All references to the progressive components of BBB were scrubbed, and ultimately the rebranding of Biden’s policies was unsuccessful. As a result, both the policy objectives and the narrative around them were muddled. When it seemed that Democrats finally crafted a new vision for economic security and environmental sustainability, they quickly abandoned it—all because of one dissenting vote.

Worse, Biden began touting his “success” on reducing the deficit, while the electorate watched millions of new dollars appropriated for wars overseas. According to data compiled by Semler (2024), Biden not only ditched his progressive agenda, but also embraced austerity for social programs but not for military spending.

In this respect, it is interesting to compare Biden’s tenure to that of Obama’s when Biden served as vice president. Biden was clearly bolder in terms of fiscal action and his policies were more worker-friendly, but he too pivoted away from them and toward deficit reduction (recall Obama’s fiscal commission).[xxv] Still, Biden presided over the fastest recovery from a recession in postwar history, with a rapid return to pre-COVID unemployment lows, a pick-up in unionization rates, and strong investment in manufacturing and construction. And while all of these are important successes, they did not speak to the public at large. Yes, Biden’s policies were very good for unions and he was the first president to join a picket line but that did not earn him big political dividends. In the US, 90 percent of workers are not unionized and many do not closely identify with union success. Often, they tend to see well-paid union workers as lucky or enjoying special privileges. Strengthening the broader working class is exactly the sort of ambition that was part of BBB and that any successful electoral strategy must embrace.

Boosting manufacturing employment is a go-to political strategy for both Democrats and Republicans and yet it is the service industry that creates many more jobs by orders of magnitude, but many of those jobs continue to be poorly paid and precarious. In the US, the employment share of manufacturing is a mere 8 percent, versus 79 percent in services. This largely explains the sizeable share of low-wage workers in the US. In 2022, 20 percent of workers in the US earned less than $15/hr and 43.2 percent earned less than $20/hr, while 58 percent earned less than $25/hr.[xxvi] Meanwhile, rural America as well as low-wage workers are no longer part of the Democratic electoral strategy. Indeed, as noted above, Democrats excessively rely on urban and wealthy voters.

What Do Voters Really Want?

In his postmortem for the election, James Carville (2025) says

It Was, It Is and It Forever Shall Be the Economy, Stupid. We live or die by winning public perception of the economy. Thus it was, thus it is and thus it forever shall be.

So, the question is, what kinds of economic policies do voters want—focusing in particular on those dissatisfied with both parties, who either sit it out or cast dissenting votes against the sitting bum du jour. We will largely rely on ballot measures that gain broad support in addition to polling data to identify popular economic policies that are largely left off the table of both party platforms in recent elections. Ballot measures indicate that voters are more progressive than either party recognizes. We will look at basic “pocketbook” measures such as raising minimum wages, paid leaves, and protecting tips, but also at other ballot measures suggesting the electorate also cares about protecting public schools, teen workers, housing, infrastructure, culture, and the arts.

1. Ballot Measures

Minimum Wages

Considering all general elections since 1998, when a ballot measure to raise the minimum wage was introduced, it passed in all cases but one. There have been 29 such successful measures (Table 1). The vast majority of these minimum wage increases took place after the Global Financial Crisis and after the last time the federal minimum wages was raised—to $7.25/hour in 2009. The overwhelming majority of the above measures were introduced in states that typically vote Republican. The only measure that failed was the CA-2024 living wage proposition (it aimed to raise the wage to $18 by 2026), perhaps because California had just passed a state law in 2023 to raise the minimum wage to $16/hour in 2024.[xxvii] In 2016, South Dakota rejected a proposition to lower the minimum wage for youths.

States and municipalities have taken separate legislative steps to raise their minimum wages. Since 2014, 28 states have changed their minimum wage laws and 63 municipalities have adopted minimum wages higher than the state minimum.[xxviii] But whatever increases they have been able to eke out, the minimum wage continues to lag behind productivity growth and remains well below living wages in most states (see the MIT living wage calculator).[xxix]

Paid Leave

Another popular worker-friendly policy is paid leave. Before the current election, 14 states (AZ, CA, CT, CO, MD, MA, MN, NJ, NM, NY, OR, RI, VT, and WA) and Washington, DC had paid sick leave mandates (Gould and Wething 2023). Federal contractors are also required to provide paid sick leave and, during the pandemic, Congress authorized a federal emergency sick leave policy, covering two weeks at full pay for COVID-related illness (with some occupations exempt). However, this policy expired, and the US remains the only developed nation in the world without federally-mandated paid sick leave.

In 2024, three additional states introduced ballot measures requiring employers to provide sick leave to workers (AK-2024, MO-2024, and NE-2024). All measures passed and all three states voted for Trump.

Tipped Workers

In 2024, Arizona voted down a measure that would have made it more difficult for the wages of tipped workers to keep up with increases in the minimum wage. Increases in wages for tipped workers passed in CO-2006, DC-2018 and 2022 (in Washington, DC, tipped workers earn the District’s minimum wage). In 2024, Massachusetts was a notable outlier, with a measure to increase the minimum wages of tipped workers to the state minimum-wage level—while allowing them to keep tips—was struck down.

Payday Loans

After the Global Financial Crisis, other pocketbook issues, such as interest on payday loans, appeared on the ballot. In all instances, voters supported capping interest on payday loans (CO-2018, MO-2012, MN-2010, NE-2020, and OH-2008). However, it should be noted that the cap is still egregiously high, typically set at 36 percent.

Education, Arts, Culture

Red or blue, states want to protect arts and culture through ballot measures aimed to restore, protect, renovate, or expand libraries, national heritage sights, local parks, or art projects. Since 1998, 38 out of 45 ballot initiatives to protect art and culture were successful. There were 13 such measures brought forward during general elections since the Global Financial Crisis, and all passed.[xxx]

Meanwhile, in 2024, three states (KY, CO, and NE) introduced and rejected measures to amend the state constitutions to allow state money to go to private schools. School choice has long been a signature Republican policy, yet two of the three states that defeated this measure voted for Trump.

Infrastructure

In California, two infrastructure investment measures passed in 2024.[xxxi] Prop 2 authorized a bond issue to go forward for public school and community college facilities, while Prop 4 proposed a bond issue for the support of water infrastructure, wildfire protection, and addressing climate risks.

2. Polling: Policies That Voters Want

Minimum wages and paid leave

Many polls corroborate voters’ progressive inclinations. Americans overwhelmingly support a $15 an hour minimum wage (69 percent of Americans), despite some differences along partisan lines (50 percent of Republicans, 95 percent of Democrats, and 64 percent of Independents). (Jackson and Mendez 2024).

Paid family and medical leave are even more popular. Eighty-five percent of Americans believe that workers should receive medical leave, while 82 percent support paid maternity leave and 69 percent are in favor of paid paternity leave. There is less consensus on how to achieve these policies, with 51 percent of Americans in favor of a government mandate, while 48 percent believe it should be the employer’s decision. Still, 74 percent of Americans believe that employers who offer paid leave are more likely to attract and retain good workers (Horowitz et al. 2017).

There are other policies Americans favor, according to polls, that did not make it onto ballots nor are they featured in most election campaigns by either party.

Taxes and Tipped workers

Ending taxes on tipped income enjoys a strong and uniform bipartisan support (73 percent of Republicans, 74 percent of Democrats, and 73 percent of Independents) (Jackson and Mendez 2024). Surprisingly, this was endorsed by both presidential candidates in 2024 although many pundits warned that this would boost the deficit. There is also widespread discontent that corporations and wealthy individuals do not pay their fair share in taxes (Oliphant 2023), with 61 percent of Americans reporting they are very frustrated over this issue and another 22 percent are somewhat frustrated. Again, while this is popular with the public, it is far less popular on Wall Street or in Washington.

A majority of Americans (61 percent) support increasing income taxes on households earning over $400,000 annually. Higher taxes on large businesses and corporations are also popular. Across partisan lines, voters believe that corporations have too much market power, including 85 percent of registered Democrats and 62 percent of registered Republicans. This is a significant shift in attitudes among Republicans over the last five years (Oliphant 2023), suggesting that the electorate may respond positively to a campaign in favor of repealing Citizens United.

Healthcare and Education: High Costs, Inflation, and Debt Relief

In 2023, Pew Research (2023b) found that the top two concerns among American voters were inflation (65 percent) and healthcare affordability (64 percent). A separate Pew (2023a) survey found that 60 percent of Americans believe that tackling healthcare costs should be a top priority for the incoming president (again only second to improving the economy). These data reflect the public’s anguish over healthcare costs, where 75 percent of the Americans gave healthcare affordability a grade of F or D (Burky 2022).

Cost reduction is overwhelmingly popular and voters are increasingly upset over hidden fees in healthcare and air travel, as well as across the service sector more generally.

Americans are also frustrated with the cost of education. A 2022 University of Chicago/NORC study found that 75 percent of Americans see costs as the biggest obstacle to attending college.[xxxii] A 2024 Pew research poll (Fry, Braga, and Parker 2024) shows that 29 percent of Americans do not believe that higher education is worth the sticker price and only 22 percent believe it is worth it if one has to take out student loans. Meanwhile, according to a 2023 Gallup survey (Brenan 2023), confidence in higher education has collapsed, with only 36 percent of Americans reporting that they a have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education, down from 57 percent in 2015 and 48 percent in 2018. Most voters think there was a drop in the quality of education during COVID, but still broadly believe in the value of a four-year degree, whether in trade schools (77 percent favorable opinion), public community colleges (75 percent), or four-year colleges and universities (65 percent) (Cecil 2024). For-profit degree-granting organizations are the only institutions Americans dislike (37 percent).

As with medical costs, Americans want government action to reduce the cost of higher education (Cecil 2024). But debt forgiveness is not very popular with the public. Student debt relief garners only 39 percent support, compared to 51 percent in favor of medical debt relief (AP-NORC 2024). While the benefits of student debt relief are significant (Fullwiler et al. 2018), there is perceived unfairness in allowing some students to get their slate wiped clean while others have worked to pay off their student loans. Surveys suggest that 54 percent of Americans support student debt relief if someone has been defrauded, compared to only 18 percent if they were not (AP-NORC 2024).

Even if Americans do not back student loan forgiveness, they overwhelmingly support free public university or college education. Depending on the survey, that support hovers between 63 percent and 80 percent of Americans (Hartig 2021).[xxxiii] Relief from medical bills tends to garner a bit more support arguably because medical debt burdens are more often seen as beyond one’s individual control or personal choices. What the public does not appreciate is that the explosion of the student debt burden took place after 2008, when “going back to school” programs served as a form of income support for unemployed Americans who were being laid off en masse, followed by the longest jobless recovery in the postwar period. For the vast majority of students, this income support came in the form of loans. And even though Pell Grants also spiked in 2010, the number of students receiving a Pell Grant has been falling since.[xxxiv] Meanwhile, according to a 2023 Marist Poll, 74 percent of Americans support doubling of the Pell Grant program.[xxxv]

The takeaway is that reducing costs of medical care and education are winning messages, but debt relief is not, per se.

Jobs and Incomes

In 2023, about half of workers (51 percent) reported being satisfied with their jobs, largely because they valued their relationships with coworkers. But when it came to pay, only 33 percent were satisfied with what they earned (Horowitz and Parker 2023). Most Americans also feel they have job security, though that sentiment is divided across demographic groups. The greatest job security is enjoyed by high-income earners (78 percent) versus low-income workers (54 percent). Similarly, 75 percent of white workers say they have job security, compared to Asian (62 percent), Black (58 percent), and Hispanic (57 percent) workers (Lin, Horowitz, and Fry 2024). Jobs may feel secure for those who have them even though the pay is inadequate, and still a shocking 56 percent of Americans believed during election year 2024 that the US was in a recession and 49 percent believed that the unemployment rate was at a 50-year high (even though it was near a 50-year low) (Aratani 2024a).

When it comes to the labor market, sentiment surveys are a lagging indicator. At best, they reflect current or most recent labor market conditions. In downturns, they drop sharply and, because recent recoveries have typically been jobless and drawn-out, it takes a long time for labor markets to improve significantly (Tcherneva 2017). The exception was the COVID recession, in which the trillions of dollars of fiscal relief restored production and jobs, leading to the fastest recovery in the postwar period—at least on paper. Pundits—especially on the Democratic side of the aisle—declared the economy to be doing well. But when the COVID relief ended and inflation rose, the economic situation for many workers did not improve in spite of various labor market indicators that suggested economic strength.

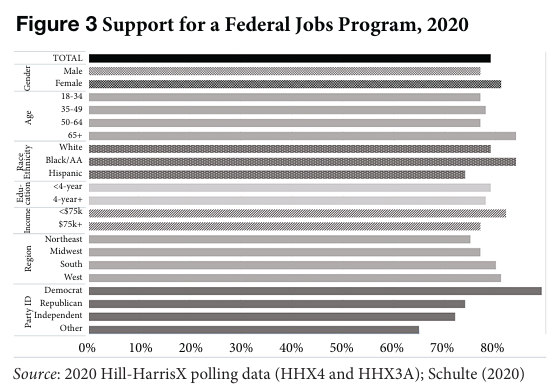

In the midst of the COVID crisis, a whopping 93 percent of Americans favored a federal job guarantee, described as “a program in which the government provides people who have lost their jobs during COVID-19 with paid work opportunities for the next few years. These jobs address national or community needs while helping people build skills for future jobs” (Gallup 2021). The job guarantee policy had been polled several times before the COVID crisis and was part of the national conversation during the 2020 Democratic primaries. Presidential hopefuls on the Democratic side who said they supported a federal job guarantee, included Kirsten Gillibrand, Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, Elizabeth Warren, and Bernie Sanders. A 2020 Hill-HarrisX poll (Figure 3) showed that 79 percent of Americans supported a federal jobs program for the unemployed with overwhelming bipartisan support (Schulte 2020).

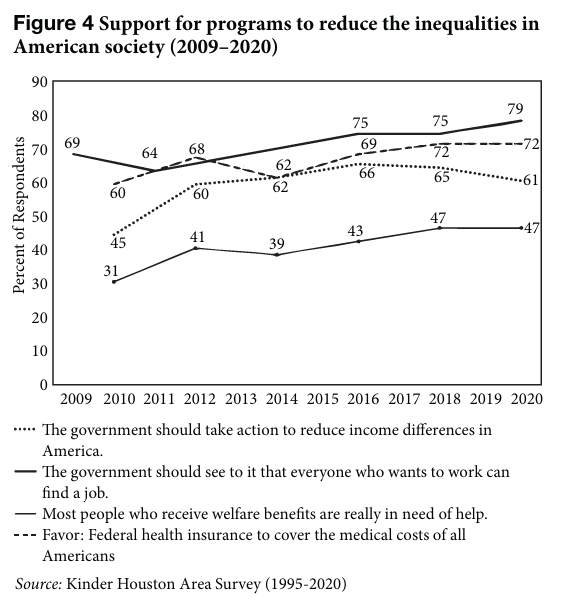

Notably, the 2020 Hill-HarrisX results were just one point above the 2019 Hill-HarrisX poll conducted before the onset of the pandemic. The support for the job guarantee does not fluctuate in the same way as other job sentiment surveys. Indeed, as documented by Tcherneva (2020), government jobs programs for the unemployed enjoy consistent support across time and partisan lines. The Kinder Houston Area survey, for example (Figure 4), shows that the popularity of the program has steadily risen since 2009 and is consistently above income support programs or other measures to reduce income inequality. (Note that federal health insurance is the second most popular policy according to this survey.)